Chess

Chequered History

Chess

by Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus, lyrics by Tim Rice

BROS Theatre Company at Hampton Hill Playhouse until 20th November

Review by Mark Aspen

What is the most serious game in the world: an ancient board game, or is it… … politics, diplomacy, romance, with all their rivalries and intrigues? BROS examined this question in last week’s production of Tim Rice’s musical Chess.

Played out against a pulsating score by ABBA’s Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus, Chess is an allegory on Cold War politics and passionate relationships. The story is based loosely on battles in the 1970s on and off the board of Bobby Fischer and Soviet Grandmasters such as Spassky, Kasparov and Korchnoi. Two Grandmasters, an American, Freddy Trumper, and a Russian, Anatoly Sergievsky are used as major pieces in their countries’ power politics and propaganda games. Florence Vassy, an Hungarian refugee, who at the outset is Freddy’s second, falls in love with Anatoly, who then defects to the West. The board is controlled by the manipulations of KGB and CIA officers within the rank and file of the national delegation, who even sacrifice Svetlana, Anatoly’s wife in a gambit to win him back to the Soviet side.

The skill of Bryan Cardus gave us a Freddy in many moods (Florence Quits contrasted with Pity the Child), but his powerful singing voice seemed at times to be dangerously close to overreaching. Paul Kirkbright’s strong acting and his widely ranged voice created an accurate portrait of the used and bemused Anatoly. Emma Mclean-Cook attacked the part of Florence with great verve, her songs ranging from the punchy to the lyrical, such as I Know Him so Well, a beautiful duet with Svetlana, played by Alison Birtle (unfortunately as her swansong with BROS).

Robert Salter played the sinister KGB officer, Molokov with energy and great stage presence against Jim Simpson’s wiry and insinuating Walter, the CIA officer, the knights on chessboard. Tom Butler created an impressionist portrayal of Arbiter, a mechanistic character with overarching control of game.

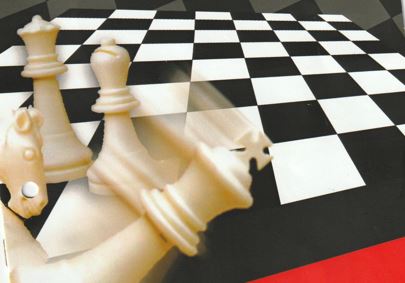

All these intrigues took place on Wesley Henderson Roe’s interpretive set, a giant chessboard, with its black and white highlighted in a red which flowed Daliesque, from the backdrop across the stage and down the apron. One detached square, which gave a point of asymmetry to the whole, was used as the location for most of the major solos, but this poxitioning soon became predictable. The squares were individually top-lit, part of Edward Pagett and Simon Roose’s extensive atmospheric lighting design, which enhanced the ambience with elements such as side battens and follow-spots.

The choreography by Caroline Smith very cleverly interpreted the mood. In the two Chess Games, the moves of pieces were elegantly replicated in the dancers’ movements; the Diplomats marched with confrontational inevitability in bridge-breaking rhythm; while One Night in Bangkok provided a sassy peep at the red-light district.

The costumes, by Lynne Shirley and Marion McLaren, contrasted black and white with vivid colour; and Joan Lambert’s costume for Arbiter underlined his robotic nature. Musical Director, Martin Wilcox, and his talented orchestra, modestly hidden in the wings, added a sparkling dynamism to the performance.

Steve Taylor, the Director brought together the BROS team in their Chess tournament, a grand-masterly product which never flagged in energy, putting over the sinister nature of the work, but colouring it with insight and humour; (the civil servants in Embassy Lament were a wickedly penned caricature). The most serious game? In the words of Molokov, “the game is greater than its players”.

Mark Aspen, November 2004

Photography courtesy of BROSTC