Mitridate, re di Ponto

Heir Raising

Mitridate, re di Ponto

by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, libretto by Vittorio Amedeo Cigna-Santi after Jean Racine

Garsington Opera, at Wormsley, Stokenchurch until 2nd July

Review by Mark Aspen

Brattish princes, pining princess, warring kings and musical fireworks, Mitridate, re di Ponto has it all, but then a young Mozart was trying to make an impression.

Famously Mozart wrote Mitridate when he was only fourteen, but this was by no means his first. He had been writing opera and singspiel before he has ten years old, and had had at least five pieces staged by the time Mitridate premiered at the Teatro Regio Ducale in Milan, on Boxing Day 1770, conducted by … Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mitridate tangles overlapping love triangles in the royal family of the eponymous Mitridate (Mithridates), King of Pontus; dangerous but even more so during a time of war, when Pontus was fighting Rome in 63BC. Sibling rivalry hits in with a vengeance, as two princes clash on political, military and familial loyalties, ramping up almost to the point of literal internecine warfare. Moreover, the brothers vie for the affections of one lady, the Queen apparent … their father’s fiancée! There are rumours that the King has been killed in battle, so another emotional instability is added to the mix.

As you can imagine this makes for an intense boiler house of passions, which Mozart taps for all its psychological steam, musically upping the pressure of the libretto, in a way that is both precociously subtle in its insight, yet youthfully exuberant in its display.

The setting is in the King’s palace at Ninfea, (in the present day very near the Kerch Bridge, which was severely damaged last October in the Russian invasion of Ukraine) on the Crimean peninsula, a strategic area fought over throughout history. However, all the action takes place inside the palace, in a space as enclosed as the protagonists’ passions. Designer, Hannah Clark’s eclectic set emphasises this enclosure. The wings comprise continuous rows of sheds, in dark grey Cuprinol, familiar yet threatening, since these act as prisons as much as exits and entrances. Upstage is a wall of bleached wood, the full height of the stage, which, as it oh-so gradually advances downstage during the opera, serves to accentuate the claustrophobic action.

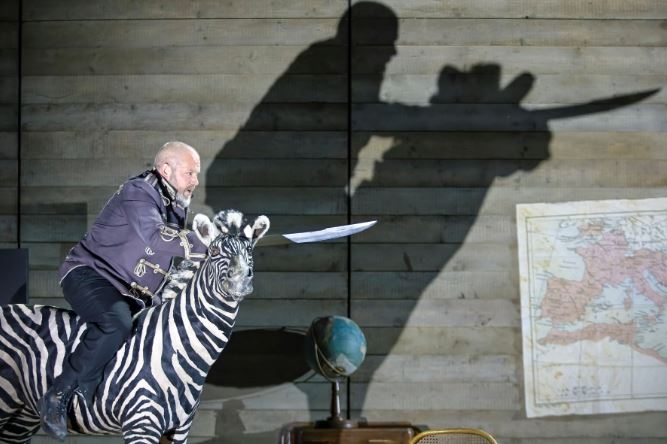

The stage props hint at the attitudes and perceptions of the characters. All is non-specific in period or location. There is a triumphant bust of Mitridate and a terrestrial globe, shades of the King’s thwarted ambitions. An elegant Regency vitrine against the rear wall has been repurposed as gun-cabinet, and an aluminium ladder leads onto its top to give a peephole view of the warring world outside. A gigantean sofa with a buzzy 1960’s print provides a louche couch for prince Farnace, the King’s rebellious elder son. Then there is the zany zebra, a full sized taxidermic specimen: extraterritorial ambitions perhaps?

Garsington’s auditorium is very open, designed to extend the park, lake and picnic pavilions as a visual whole. For Mitridate it works well in accentuating, by sheer contrast, the claustrophobic feel of the opera. It does however demand a lot from the lighting designer, in working in conjunction with natural light. Malcolm Rippeth incorporates nature and artifice skilfully. The lowering light of the setting sun in an evening performance gives an urgent sense of inevitability to the plot.

During Mozart’s musically scene-setting Prologue, some finely placed acting tells much of the backstory. We feel the anxiety of Aspasia, Mitridate’s betrothed queen, as she paces nervously around the space; the ennui of Prince Farnace, oozing dissipation as he snoops, swigs and sprawls from side room to whisky bottle to sofa, where he idly rearranges toy soldiers; and the concern of the upright Prince Sifare, Mitridate’s younger son. All wear mourning black, having learnt from Arbate, the Governor, of the presumed death of Mitridate in battle, except for Farnace. He swans around bare-chested in flowing purple silk dressing-gown. The scene as a whole is a brilliant character study.

Mitridate however seems to have encouraged the rumour of his death (“an exaggeration” Wilde might have said) to worm out what might be going on behind his back. The loyal Arbate is certainly complicit, for he keeps running up the ladder to the peephole to view the hinterland. Tenor John Graham-Hall’s Arbate, stiff-collared and buttoned-up, apprehensively circles the action, appalled by what is unfolding, yet impotent to prevent it.

Aspasia is the most compromised and conflicted character. Elizabeth Watts, dressed in Victorian widow’s weeds, exudes Aspasia’s distress, torn between fidelity to her fiancé and her hidden feelings for Sifare. She feels totally trapped. Watts’s lustrous soprano is well suited to Aspasia’s aria of outpouring to be free (from her obligation to Mitridate, from the unwelcome attentions of Farnace, from the palace) at the opening of the opera, thorugh to her emotional cavatina, Pallid’ombre Pallid’ombre, che scorgete dagli Elisi (pale shadows seen from Elysium) at the conclusion of the opera, when she deliberates over Mitridate’s demand that she should poison herself. The controlled coloratura in Watt’s impassioned delivery is superb.

In the breeches role of the self-effacing Sifare, Louise Kemény portrays a serious, worried-looking, gentle prince. Her clear soaring soprano is very affecting and in arias Soffre il mio cor (May my heart suffer) when Sifare at first reveals his love for Aspasia; and in Lungi da te, mio bene (far from you my dearest), when they decide to part, Kemény is exquisite in its expression of yearning.

In an opera that is largely a series of gorgeous party-piece arias, there is one duet, a passionate number between Sifare and Aspasia, Se viver non degg’io, se tu morir (If I shall not live, if thou shalt die) the pre-interval cliff-hanger, which highlights the skills of Watts and Kemény, both of whom are making their Garsington debut. The French horn is one of Mozart’s favoured instrument, and here he allows it a starring moment. Ursula Paludan Monberg, as the horn soloist excels in this virtuoso moving lament. And, she had given us a foretaste with an obbligato sequence as a coda to Lungi da te.

Also (surprisingly) making a Garsington debut, is world renowned countertenor, Iestyn Davies in the enviable role of Farnace. Davies clearly relishes the part of the petulant playboy prince, who is bored, self-indulgent and out to make mischief. (It was difficult in a week when a modern day version of this prince was airing his own grievances in the High Court in London, not to draw parallels.) Davies is brilliant, his burnished bell-like countertenor is clear, concise and full of character. He is also an intelligent actor, who is able to round-out his character to that, when the treacherous prince eventually shows honesty and nobility, we believe him. In his final aria Già dagli occhi il velo è tolto (the veil is lifted from my eyes) his sincere conviction is dramatically convincing, and is musically outstanding.

You see, Farnace had been collaborating with the enemy, in the form of the Roman tribune, Marzio. Welsh tenor Joshua Owen Mills makes an assured Marzio, wax-moustached, jackbooted, Mussolini-era officer. He has an imposing resonant voice, with little opportunity to fully show his acting skills, he comes into his own when Farnace assassinates Marzio at the end of a very vicious dagger. Here is reality, as he twitches and writhes whilst his life-blood ebbs.

The only person who stands up for Farnace is the Princess of Parthia Ismene, promised as a bride to the very reluctant Farnace. Soprano Soraya Mafi, who made a vivacious Suzanna in Glyndebourne’s Marriage of Figaro last autumn, sparkles as an empathetic Ismene, sweetly forgiving of Farnace’s peccadilloes. She is very much the peacemaker, and pleads with King Mitridate to find peace of mind in accepting Farnace. The aria, So quanto a te dispiace (I know how it displeases you) wonderfully demonstrates Mafi iridescent delivery brought to a decorated coloratura. She may be Farnace’s poodle, but it is a little unkind of the costume design to make her quite so much literally so.

What of King Mitridate himself? Robert Murray has huge stage presence in this role. We first see him, a crushed figure, having retreated from the battlefield. He bursts wearily through the door, dragging a huge trunk, bedraggled and beaten. He demands of himself, respira !, and breathe he does … fire and ire. His opening cavatina aria, Se di lauri il crine adorno … almen non porto il volto di vergogna (If laurels do not adorn my hair… at least I am not yet disgraced) sets his defiant stance. Murray punches home his point in a powerful resonant tenor voice. Vocally, the part is hugely demanding, and dramatically requires quite an emotional journey, as Mitridate descends almost to a state of paranoia, trusting no-one (unjustified) and believing himself threatened by his own family (justified), and pumping up bravado, as he plans to march against Rome itself and its military might.

When Mitridate makes his second return from battle, he is fatally wounded and falls on his own sword. Cue the only other non-solo passage, an heroic quintet Non si ceda …(do not surrender…)

Mitridate, re di Ponto could easily descend into melodrama, but director Tim Albery steers well clear of these rocks in a balanced and thoughtful production that honours the intentions of the young Mozart. Amazingly for a fourteen year old Mozart creates characters that are very three-dimensional and human in their ambiguity. Some might see Farnace or Mitridate as the villain, but Farnace redeems himself at the end, and Mitridate is at heart that unfashionable creature, a patriot, who wishes the best on his country.

Mozart also makes the musicians and singers work hard through a sophisticated score. His original score of six hours, astonishingly written in a few months, has been skilfully edited to two enthralling hours. Conductor Clemens Schuldt is well up to the task, clearly understands Mozart approach to his virtuoso breakthrough and gets the comprehensive skills of The English Concert honed to their best.

If Mozart was throwing everything into the ring to make an impression in the Milanese ducal court back in 1770 he certainly succeeded. And in 2023 Garsington Opera have certainly succeeded too, in a production of Mitridate, re di Ponto that captures the young Mozart’s exuberance and virtuosity the psychological tensions and emotional turmoil of a court under siege externally and from within.

Mark Aspen, June 2023

Photography by Craig Fuller and Julian Guidera

Trackbacks & Pingbacks