A View from the Bridge

Miller’s Tale

A View from the Bridge

by Arthur Miller

Headlong at the Chichester Festival Theatre until 28th October and then the Rose Theatre Kingston until 11th November

Review by Patrick Shorrock

Arthur Miller’s stock has fallen somewhat. The Crucible and Death of a Salesman are undisputable masterpieces. But they are now school set texts – which doesn’t always help them live outside the curriculum – and the later plays are hardly ever done. I can remember desperately undistinguished revivals of All my Sons, The Price and The American Clock, which did nothing to add to Miller’s credibility. But there was also Ivo Von Hove’s sensational production of View from the Bridge at the Young Vic in 2014. So the question prompted by this revival is: can this play survive in a more ordinary production?

It can, but only just. Originally a one act play in verse, it was latter rewritten as two acter in prose. There is rather too much prolix and unnecessary exposition, although there are some interesting ideas floating around. Is it only heroes and royalty (Hamlet, Lear, Oedipus or Antigone) or middle class intellectuals (anything by Ibsen) who deserve to be the subject of tragedy? Miller suggests that the tragedy of an ordinary docker is also worthy of our attention, but the result is rather like a wordy Cav and Pag without the music. Docker Eddie and Beatrice have brought up their orphaned niece Catherine. They agree to provide a home to Beatrice’s cousins Rodolfo and Marco (a brooding Tommy Sim’aan), who are illegal immigrants, trying to make some money in America, where there are more jobs and opportunities than in their native Sicily. (The play’s acceptance of the benefits of a free market in labour is very different from now when fears of the immigrant are being stoked up for political ends.) Eddie has hidden desires for Catherine and is angry when she takes up with Rodolfo. The lawyer, Alfieri, who narrates the piece and functions as a clunky chorus-cum-narrator, tells us that it is all going to end horribly – not that it is exactly necessary to point this out. What I will say is that the death is not the one that I was expecting.

Previous productions have very much seen Eddie as a force of nature with superhuman charisma, uncorrupted masculinity at bay, but Jonathan Slinger plays him as a lot more ordinary than that: less scary and more credible. This lowers the dramatic voltage, which will be a disappointment to collectors of ‘big’ stage performances, but is, I suspect, more true to life. Old fashioned masculinity seems increasingly suspect these days – rightly so; not so much a heroic ideal, as a way of consoling yourself for the miseries inflicted by capitalist exploitation by means of passing them onto other family members while insisting on treating women as possessions. (Not for nothing do the gramophones on stage play “I’m gonna buy a paper doll that I can call my own. A doll that other fellows cannot steal.”) The myth of the natural dignity of manual labour – when it is simply a way of encouraging people to collude in their own exploitation – is shown as something that it is in no man’s interest to expose, whether it is those with nothing else to derive their identity from, or middle class intellectuals wanting to find something to admire in everyone, or those profiting from an exploitative status quo who don’t want the boat to be rocked.

To be fair to Miller, the dinosaur version of masculinity on display here is shown as ultimately destructive if not downright bonkers, with crazy notions of honour that seem all too derived from a Verdi opera and simply make life even more impossible for those already struggling. There is certainly little to admire in it, unless, perhaps, you are D H Lawrence. (To be fair, much the same can be said about many protagonists of Greek Tragedy, with their tragic flaws that are often no more than high-handed arrogance). What is rather less clear is whether Miller is admiring of – or ambivalent about – Eddie, but it seems all too probable that, in the 1950s, when he wrote the play, he had yet to be enlightened by the insights of feminism. Certainly Eddie finds it all too easy to ignore the good sense of his wife Beatrice (Kirsty Bushell) who is anything but a downtrodden cypher.

Director Holly Race Roughan tries to impose some modern theatricality on the proceedings, although the production doesn’t always rise above modish window dressing (the cast carrying chairs aloft through streams of dry ice to menacing music). She changes the gender of Alfieri (now played by Nancy Crane), which is harmless enough, although it seems unlikely that a female lawyer in the 1950s would have had many clients unless her prices were very cheap. It also means we lose that sense of Alfieri as being complicit in patriarchy as well as observing the damage it does. If Crane’s commentary comes across as redundant, clunky and anti-climactic, that it largely Miller’s fault. (To be fair, there is a similar effect when people comment on Shakespeare’s equally bloody climaxes, as you wonder why they don’t just cut the text at that point.)

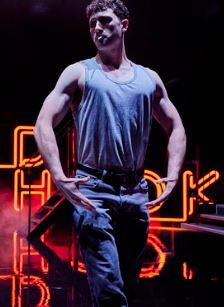

There is a fine shiny black set from Moi Tran, with the place name Red Hook – home to many migrant Italian dockworkers – in red neon at the back of the stage. There is a hint of deep waters with something nasty lurking underneath the infinity pool. Rodolfo (Luke Newberry) suggests an alternative version of masculinity to Eddie’s that is willing to indulge in pleasure, admit to an interest in music, and have potential for empathy. This means that Eddie suspects that he is not a ‘real’ man, and only interested in Catherine (Rachelle Diedericks; somewhat bland in a bland role) in order to get a green card. Elijah Holloway, in his professional debut, plays one of the stevedores, but also appears from time to time in ballet gear, both showing off his substantial muscles and dancing on his toes like a ballerina, presumably a symbol of the ambivalence and wokeness that Eddie dreads.

The ending is suitably wrenching and bloodstained – this is not a feel good evening – but does provide food for thought on the way home.

Patrick Shorrock, October 2023

Photography by The Other Richard