The Mongol Khan

Wars of Succession

The Mongol Khan

Hero Entertainment, Wild Yak Productions and Maktub Productions at the London Coliseum until 2nd December

Review by David Stephens

Written in 1998 by the late, great Mongolian writer, Lkhagvasuren Bavuu, and based on his original play, A State Without a Seal, the beautifully crafted piece The Mongol Khan tells a cautionary tale of imperial greed and the determination of a fictitious leader of the Hunnu people, Archug Khan, to maintain stability and the enduring legacy of his empire, even at great personal cost.

Considered by many as the early statehood history of Mongolia, the Hunnu were, at the time, the largest tribe of nomadic people to have walked the earth. Amassing as a result of the wars and conquests of rival marauding tribes, the Hunnu soon became a mighty force, often aggressively challenging China for land; and often rampaging through Chinese towns and villages to pillage goods and to weaken their enemy in a bid to secure themselves a footing as an emerging power. It is at the very peak of Hunnu power that the fictitious tale of The Mongol Khan is set.

The plot revolves around the birth of two princes, three days apart; the first, and therefore heir to the throne, born of the Archug Khan’s wife, Queen Tsetser and the second of his consort, Gerel. As he has not shared his wife’s bed for many years, his immediate suspicion over the legitimacy of the apparent heir to the Hunnu Empire begins to eat away at him and he decrees that his son with Gerel should be declared his rightful successor.

We soon learn that his suspicions are well founded. Queen Tsetser has been privately entertaining Egereg, the Khan’s Chancellor and trusted advisor, and it is he who has fathered the child. Egereg is determined that his blood-line will rule the Hunnu and, together with the estranged Queen, plots to swap the infants and then reveal all once the Crown Prince comes of age. Succeeding in this plan, and with their cuckoo securely in place within the palace ‘nest’, Egereg and Tsetser bide their time.

As the infant matures, however, his petulant ways convince Archug Khan that the empire cannot be entrusted to him and, putting the future of his own people before that of ‘his’ son, he then decrees that the ‘illegitimate’ child he bore with Gerel should be his successor.

A thirst for power soon gives way to rising anger, and terror and bloodshed follow quickly on. As the play ends, the now heir-less Khan pledges to continue his reign for the good of the Hunnu people. His great personal sacrifices would all made for the good of the state.

Although this sacrifice sounds highly aligned to communist ideologies, and should, therefore, be appealing to modern communist states, it is interesting to note that the play has recently been banned by Chinese authorities. Before the production moved to London, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that, although originally approved by Chinese authorities for performance in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia (China’s northern-most province), it’s opening night was cancelled following a suspicious power-cut only thirty minutes prior to curtain-up. The production team were then immediately expelled from the building and forced to find an alternative home for the production. However, when attempting to retrieve their £2m worth of costumes, set and equipment, they were denied access to the theatre. They have since complained of being put under regular state surveillance by the Chinese.

The reason for this is the increasing concern among Chinese authorities of the growing sense of nationalism among the Mongolian people. Activists have complained that their history, traditions and culture are being systematically eradicated by the Chinese state who are keen to assimilate their dwindling population into the local Chinese majority. In September, around the same time that the production’s opening night was forced to close, all Mongolian-language schools in Inner Mongolia were forced to switch to teaching exclusively in Chinese. This, following the forced exile of many Mongolian language teachers.

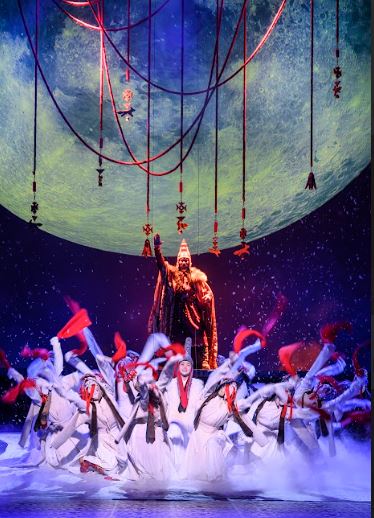

All of the above have made director, Hero Baatar, more determined than ever to bring his production to the stage and it was certainly enthusiastically received by a highly charged and, one sensed, sympathetic audience on one of its first outings on the stage of the London Coliseum. Quite simply, the production is spectacular, in every sense of the word. Its seventy-strong cast, exquisitely adorned in traditional costume, excelled in each and every area of theatrical performance. Traditional dances were immaculately choreographed and delivered a wonderful sense of Mongol spirit, identity and legacy and the acting was superlative.

However, this production takes choreography to an entirely different level and one never-before-witnessed by this reviewer. With each spoken line, one witnesses the physical shift in each character’s emotions through the response of the individual’s spirits, represented on stage by a number of perfectly synchronised dancers. Each character has eight spirit bodies mirroring their movements at all times, sometimes immediately replicating, sometimes echoing and, at the other times, even projecting forwards. Picture a camera effect that shows the individual moving forwards but retains their previous position visible by leaving previous frames in view. This almost ethereal trail is the tremendous effect witnessed by the audience. On one occasion, the Khan swings his sword towards Egereg from across the stage and, almost like a scene from Mortal Kombat, his spirit-bodies then project forward, one ‘frame’ at a time, each slightly more progressive with their sword swing and fighting stance and each in perfect synchronisation, until the foremost body engages in combat with the spirit body of Egereg. The effect is jaw-dropping and the level of complexity involved in making this happen, scene after scene, is simply mind-bending.

The Mongol Khan a complete masterpiece and a production not to be missed.

David Stephens, November 2023

Photography by Katja Ogrin