Suite in Three Keys

Swan Song

Suite in Three Keys

by Noël Coward

OT Productions, at The Orange Tree in Richmond until 6th July

Review by Harry Zimmerman

Marking the fiftieth anniversary of Noël Coward’s death, and the 125th of his birth in nearby Teddington, The Orange Tree in Richmond offers a rare opportunity to see a trio of Noël Coward plays, Suite in Three Keys, his last completed writing for the theatre. This production represents the first complete revival of this work for a generation.

Directed by Tom Littler, and featuring Stephen Boxer, Emma Fielding, Tara Fitzgerald and Steffan Rizzi, the plays are conceived as a loose trilogy, with all three of the stories set in the same Swiss hotel suite. They are subdivided into the standalone A Song at Twilight and the double bill of the romantic Shadows of the Evening and comedy Come into the Garden, Maud.

The plays are performed as originally intended, with the double bill alternating with the third, longer play, The Orange tree production also enables the audience to enjoy all three plays in one complete show day.

In a luxury Swiss hotel suite in the middle 1960s, three separate stories unfold:

Shadows of the Evening is the most serious of the three offerings in both tone and theme. It depicts the relationship of a terminally ill man with his mistress and his estranged wife.

Linda Savignac receives a visit from Anne Hilgar. They were once close friends, until Anne’s husband, George, left her for Linda, seven years ago. Anne has come from London at Linda’s request to discuss George’s health. During a routine examination, inoperable and terminal cancer has been detected. Linda explains that George has not been told, and she wants to discuss which of them ought to break the news to him.

Shafts of strongly expressed emotion permeate the carefully constructed dialogue, which swiftly and economically delineates the nature and motives of the characters, especially the females, Linda’s restless nervous energy being nicely balanced by Anne’s clear-sighted control.

Themes of stoicism, loyalty and muted emotional openness are never far from the surface, summed up by Hugo’s observation that “…every schoolboy has to face the last day of the holidays.”

By contrast, Come into the Garden, Maud is a witty reflection of the love triangle that enables Coward to satirise the awkwardness when Americans and Europeans are faced with understanding and adapting to each other’s culture.

The play depicts a middle-aged American couple, Anna-Mary and Verner Conklin. She is querulous, irritable, domineering, and a social climbing snob. There is much humour to be mined from this particular characterisation, especially when compared to the laid back, laconic and philosophical Verner, desperate for a quiet night. That is until Maud Caragnani enters the fray, and very much upsets the apple cart…

Unlike the emotional intensity of Shadows of the Evening, this is a light-hearted piece which allows a number of trademark Coward witticisms to be crisply and unequivocally delivered, albeit with a bludgeon rather than a rapier.

The energy of the characterisation drives the narrative along, but this is more than a witty confection of one liners and cultural parody. Amidst the freneticism, we see Verner wondering if he can grasp a suddenly presented final opportunity to salvage a last burst of happiness, a final hurrah of passion and excitement before the ossification of late middle-aged convention and expectation sets in.

The longer, two-act third of Coward’s trilogy is A Song at Twilight. This is a tension filled drama that takes place across a single night as two former lovers meet, each with differing recollections of the significance of their relationship and with very different intentions, and prompted by the publication of a memoir.

World-famous author Sir Hugo Latymer is growing old, rude, and haughty. He is attended to by his long-suffering wife and former secretary, Hilde. He nervously awaits the arrival of an old flame, actress Carlotta Gray, with whom he enjoyed a two-year love affair more than forty years ago. What can she possibly want now? Revenge for his uncharitable characterisation of her in his recent autobiography? Money, to compensate for a second-rate acting career in the States? But it turns out Carlotta is writing her own memoir, and wants something much more significant than cash…

This is the highlight of the trilogy. A Song at Twilight is about harbouring secrets, regretting missed opportunities and the inherent tension between the importance of one’s work and the cultivation of one’s reputation.

In addition to providing the foundations for sharp wit, repartee and verbal dexterity, this play takes a series of sharper, darker turns that deal with the consequences of creating a carapace of concealments and deceptions that keep our most intimate relationships — with ourselves as well as with others — hauntingly unresolved.

Hugo and Carlotta’s reminiscences of old times together soon moves from the sentimental and waspish to something much more tense, dark, and adversarial.

The cut and thrust of the dialogue becomes a powerful, at times almost venomous, game of cat and mouse, which draws the audience in effortlessly. The shifting power-play between Hugo and Carlotta is well delivered, with the frequent preciseness of witty one-liners alleviating the tension, but never distracting from the main themes of ageing, trust, regret, forgiveness and the repression of past lives and past sorrows. It is a study of how, try as we might, we can never escape who we really are.

This is a challenging trilogy of plays, which tests the abilities of the cast to their utmost. Each actor has to deliver a very different set of characterisations throughout their three performances, and, in lesser hands, some of the emerging themes and concepts would be stifled. We are, though, immensely fortunate to have a talented set of actors to deliver the trilogy.

Emma Fielding is clearly relishing playing such diverse roles as a slightly buttoned up, stiff upper lip Englishwoman in Shadows of the Evening, a monstrously controlling American social climber in Come into the Garden Maud and a thoughtful, devoted but independent German wife and literary manager in A Song at Twilight. She is always watchable, always believable, and displays a remarkable authenticity in the different accents required of her.

Similarly, Tara Fitzgerald utterly convinces in her roles as the disruptor and catalyst for change across all three pieces. A set of compelling performances is topped off by her superb characterisation of the archly knowing, sassy and supremely self-confident Carlotta.

Stephen Boxer is a magnificent anchor point for much of the action across all three plays. He is moving as the dying George, amusing as the bored and clear-eyed Verner and memorable as the arrogant, haughty yet ultimately torn and haunted Hugo.

All three give delightful performances.

A word of praise here for Steffan Rizzi’s fabulous portrayal of Felix, the waiter. Felix has a great voice, a winning manner, and is the epitome of understated professionalism and tact. He acts as the unifying factor across each of the plays and is never less than engaging and funny. He deserves a huge gratuity from all the hotel’s guests!

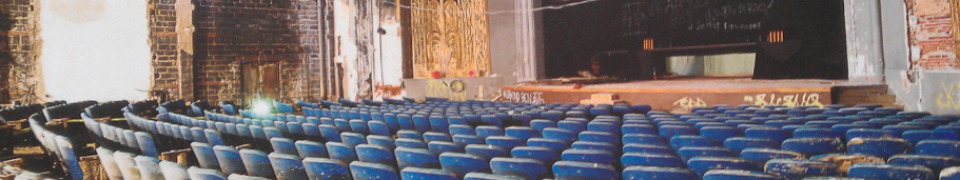

The set effortlessly evokes the slightly faded grandeur of a hotel suite which might just have seen better days. Assorted piles of papers and books and a huge cut glass table lighter create a realistic mise en scene.

The delivery of these plays in the round is also very important, drawing the audience into the intimacy that prefigured much of the action. At one stage, a number of audience members were looking at the chocolate soufflé enjoyed by Hugo and Carlotta during their dinner in A Song at Twilight, with very envious eyes!

The costumes are entirely appropriate to the mid-1960s milieu, as are the occasional strains of Satisfaction from neighbouring rooms, not to mention the hugely enjoyable renditions of 60’s classic songs in Italian by Felix during the interval!

Presenting Suite in Three Keys is a challenging undertaking. The plays are very dialogue heavy, and, particularly in the two one-act plays, the narrative is sometimes a little stodgy, and could benefit from a degree of judicious editing to move things along quicker. It can also be argued that the plotting of both Shadows of the Evening and Come into the Garden Maud rests a little too heavily upon stereotypical scenarios, with the endings being fairly obvious from a long way off.

However, that having been said, Suite in Three Keys gives us a glimpse of a playwright that is wrestling with the changing social conditions of the 1960s and the problems of status, celebrity, marital discord, regret, and loss that affects his characters in the autumn of their lives.

Suite in Three Keys is not Hay Fever or Private Lives. This collection deals with a sober consideration of the accumulated impacts of accomplishments, fame, and social standing on a life nearing its end. The effects of the arrival of a long-buried secret, an unresolved issue, or an opportunity to break away, provides the catalyst for the key characters to review what is important in life, and how best to achieve an accommodation with the future, however long or short that may be.

The Orange Tree is to be congratulated for its foresight and creativity in offering its audience a rare opportunity to see a very different side to the Noël Coward’s canon.

Harry Zimmerman, June 2024

Photography by Steve Gregson