Filumena

Two Weddings and No Funeral

Filumena

by Eduardo de Filippo, adapted by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall

Bill Kenwright and Theatre Royal Windsor at Richmond Theatre until 23rd November

Review by Mark Aspen

Comeuppance, nice old-fashioned word. When Filumena opens with the revelation that the wealthy Domenico Soriano has been artfully tricked by his live-in mistress of 35-years, one might think that here is a straightforward comedy about an arrogant man’s comeuppance. But no, the comedy is laced with pathos, as it cleverly probes the potency and quirks of lasting relationships, the strength of maternal love, and the sanctity of human life.

Filumena is a clever and stylish work of art, brilliantly written, brilliantly acted and brilliantly presented. Director Sean Mathias has used all his established skills to package a beautiful jewel-box of a comedy.

Don Domenico’s house is the grandest in Naples, and designer Morgan Large’s set is certainly grand, certainly stylish and, well, wow! It is Rococo extravagance from its ceiling painting of putti, its silk-papered walls, its tall arched windows, to its marble floor, and beautifully lit by Nick Richings. An active pre-set, in which domestic staff busy themselves preparing the room, gives chance to admire it. It is late spring, the heat of a Neapolitan day is subsiding and suddenly Don Domenico and Filumena Marturano burst in.

They are in the midst of a furious row. Filumena, following her “deathbed” marriage to Domenico by the local priest in articulo mortis, has just made a miraculous recovery from her imminent demise. His twenty-something new lover, Diana, is waiting outside and all is set for an intimate dinner for two. Filumena is rightfully going to put a stop to this. She is now his wife after three and a half decades of their affair, since they first met … in a brothel. During this time she has not only been chatelaine to this mansion and his other houses, but has helped oversee the shops and factories of his confectionery empire.

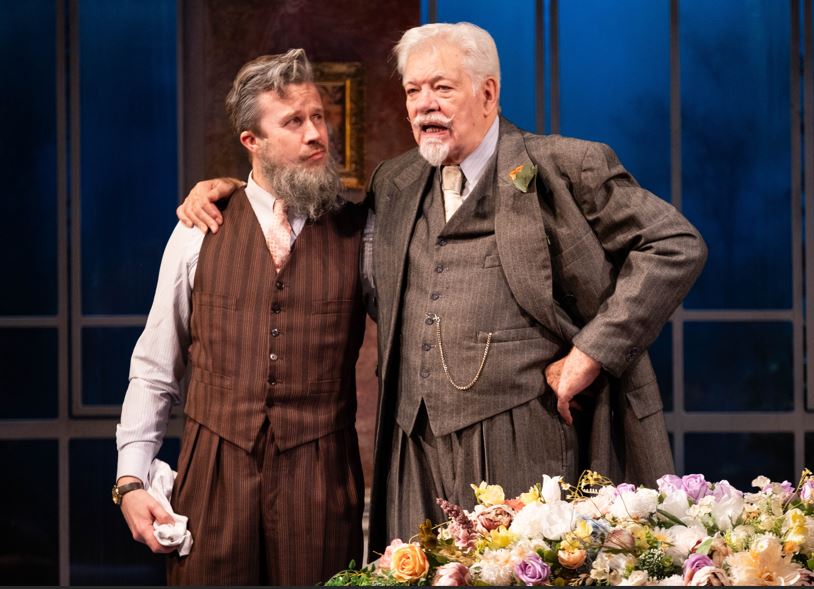

The fireworks of this opening scene are given huge energy by Matthew Kelly and Felicity Kendal. Kelly gives a towering (in all senses of the word) performance as Domenico, suave and urbane, yet stubborn and self-centred; sharp and quick-witted, yet acerbic and highly cynical. “Foo” Kendal has kept the sparkle and charm that were her hallmark still as fresh and lively as when she was first seen on stage, as she portrays the resilience and wiry wit of a fighter, a wily woman who, via the streets and brothels of Naples, has pulled herself from poverty to power, quite literally from rags to riches. The juxtaposition of 6ft 6ins Kelly and petite Kendal underlines the nature of stolid Domenico and feisty Filumena’s relationship.

Witnessing their altercation are Alfredo Amoroso, Domenico’s friend and drinking companion, with whom he had shared the excitement of travel and of horses, and the doubtful pleasures of the whore-houses; and Rosalia Solimene, Filumena’s elderly confidante, her trusted and loyal servant, and housekeeper to the Domenico household, who also shares that history of abject poverty.

Jamie Hogarth plays an Alfredo, now grey and mellowed, with an air of world-weariness merging into amused curiosity. Julie Legrand is wonderful as Rosalia, spritely and incisive, with a quicksilver wit, and not afraid to be insubordinate or provocative. The two roles are largely those of observers to the action, a bit like a Greek chorus, although they do help the plot along, but both actors bring out the idiosyncrasies of their characters, often with something as subtle as sideways glance. Legrand has an affecting scene, in which Rosalia tells her backstory, and she puts real bite into its poignancy.

Jodie Steele plays Diana, the precocious and presumptive new-model lover, with the butterfly movements and the translucent flirtatiousness of a would-be seductress trying to stake a claim.

However, the plot of Filumena has more twists and turns than the Stelvio Pass. Domenico is not going to let Filumena get away with her subterfuge and he briefs the lawyer Nocella to arrange to have the marriage declared null and void. Ben Nealon plays Nocella, whom Domenico treats with unwarranted distain, as a man trying to be professional under the rather strange circumstances and putting aside his unease. Nocella, however, comes up with the goods: it is an open and shut case, under Article 101 of the legal code (or is it Article 147).

And talking of cases, there are some inspired little touches by Mathias and his creative team. When Nocella takes a massive portfolio from his briefcase and drops it on the table, there is a big cloud of dust. Previously Domenico had invited Nocella to sit to the table, but had denied him all the chairs, indicting the footstool instead. Maintaining his composure and refusing to be browbeaten, Nocella brings it to the table and sits on it. Moreover, the atmosphere of the play is maintained by Dan Samson’s soundtrack of opera intermezzi during the scene changes.

As a riposte to Domenico’s annulment of their marriage, Filumena pulls out of the hat a secret from her past life, that she had had three sons during her time in the brothels of Naples. Furthermore, she has stolen from Domenico throughout their lives, without the sons’ knowledge, to support, educate and set them up in business.

When she became pregnant, the other girls in the brothel said she should “get rid” of the child, but her conscience would not allow her kill the child in her womb. She believes that “children are children, and they’re all equal”. (The saying, I figli sono figli e sono tutti uguali has become an established adage in Italy.) Filumena, in exchange for accepting the annulment, wants Domenico to legitimise them by allowing them to adopt his family name of Soriano.

Filumena’s three adult sons are Umberto, an accountant; Riccardo, a bespoke shirt tailor; and Michele, a “sanitary engineer” … “plumber”, Rosalia interjects. She invites them to come to house where she can announce to them that she is their mother.

These characters have a long but rapid emotional journey. Family man Michele accepts the situation and embraces it welcomingly, the vain Riccardo want to reject the idea, while Umberto holds his peace and ponders the implications. Gavin Fowler plays Umberto as a reticent and thoughtful man, a little shy, but able to hold his corner when the push comes (literally) to the shove. Fabrizio Santino’s long-haired, white-suited Riccardo is, in contrast, blustering and self-important, impatient to be away to tend to his business. George Banks depicts Michele as a genial, easy going sort, but when he arrives after Riccardo, it is not long before a squabble breaks out between them and soon deteriorates into a three-way brawl, (sibling rivalry rearing its head incognito?).

In another twist to the tale, when Domenico refuses to grant “the bastards” his name, Filumena pulls out her trump card … one of her sons is his!

Pitching the acting register in a tragi-comedy like Filumena is difficult, but all the cast steer away from caricature to heightened presentation that enhances the emotional edginess of the play whilst bringing out the full punch of the comedy with impeccable timing. Not that animation is lost. Sarah Twomey adds a different humour as Lucia, the sassy and often quite cheeky maid, with great shoulder acting, and puffing out her, (um) chest, as she asserts her part in the proceedings.

There are some nice cameo roles at the beginning and end of the play. The head waiter from a nearby fine-dining restaurant and his assistant bring in the intimate dinner that is intended, post-mortem Filumena, to woo pre-coital Diana, an amuse-bouche as one might say. Lee Peck, ably supported by Eliza Le Youzel Teale, paints a vignette of the hapless and bemused waiter, slowly realising he has made a faux pas and not quite sure how to get out of it. Hilary Tomes plays the local dressmaker, Teresina, polite yet frustrated at being the scapegoat for Filumena’s wedding dress not being quite reconciled with Filumena’s idea of her own measurements.

“Wedding dress?” you may ask. We come to the much shorter second half of the play. It is ten months later, and things have moved on. The table is piled so high with flowers that it would put Chelsea to shame. The final twist is that a wedding is in the offing that evening, what Domenico calls his “reparation marriage”. He has tried in vain to find out which of the three sons is also his, but he has mellowed and finally accepts them all.

In the event, Domenico’s comeuppance is conciliated. (Along the way we discover that Matthew Kelly has a fine singing voice. His la donna e mobile is exemplary.)

Finally, Filumena, the woman who never learnt to cry, weeps at it all.

Mark Aspen, November 2024

Photography by Jack Merriman

Trackbacks & Pingbacks