Don Pasquale

Marry in Haste, Repent at Leisure

Don Pasquale

by Gaetano Donizetti, libretto by Giovanni Ruffini

West Green House Opera at the Green Theatre, Hartley Wintney, until 27th July

Review by Mark Aspen

West Green pulls out quite a surprise for the culmination of its Silver Anniversary Season, and it is a right bonzer, taking Don Pasquale down-under. It casts Grant Doyle, a fair dinkum Aussie, in the leading role of Pasquale, and even the surtitles are in Strine!

The production is a thinly-veiled tongue-in-cheek homage to West Green House Opera’s founder, the redoubtable Marylyn Abbott, whose garden design and opera production careers have run in parallel on both sides of the globe. Formerly part of the management of the Sydney Opera House, she bought the lease of West Green House in 1993 order to create the perfect English garden, bringing with her expertise gained in setting up the renowned Kennerton Green Gardens in Mittagong, New South Wales. And it was Marylyn Abbott who inaugurated West Green House Opera in 2000 with The Marriage of Figaro. Over fifty productions later along comes Don Pasquale in bushwhacker hat.

Don Pasquale had its premiere on 3rd January in sophisticated Paris. In the same year, 1843, Richard Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer premiered on 2nd January in then stodgy Dresden, amazingly different operas. Wagner took eleven years to write The Flying Dutchman, whereas Donizetti just eleven days to compose Don Pasquale. Ruffini, concurrently writing the libretto, complained that he could hardly keep up. He said he was treated like “a working stonemason of verses” cutting, craving and reassembling elements of an old story, and delivering the libretto by the hour. But he was full of admiration for Donizetti’s ability to “dash off a long duet in an hour”. Yet, “moreover, it will be beautiful”.

Certainly there is an urgency in the work and, in the hands of director Richard Studer and conductor Jonathan Lyness, it fairly skips along, having great fun on the way, but never losing the clever complexity and intrinsic beauty of the music, both vocal and instrumental.

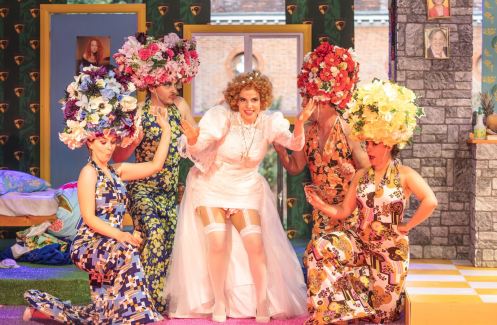

The colourful set, conceived by Studer, is full of witty references to place it in New South Wales in the 1970’s, and is complemented by brilliantly researched costumes by Jill Rolfe and her team, including cricket shirts hinting at the Australian national squad of that time, plus tee-shirts with racy slogans, and bell-bottomed zany body suits for Pasquale’s indolent servants. The latter also have ultra-flamboyant floral headwear, by Ben Johnson-Rolfe, to complete the exuberance of their get-up, sort-of blossom possums.

The set itself comprises three areas, a bedroom with adolescent-style duvets on a low divan; a kitchen with plastic table and chairs in primary colours, and the garden with tool-shed (or thunderbox?). The Australian flag hangs limply on a pole outside. All is clean and fresh, unlike it’s occupants, Ernesto and late-teen chums, who come come staggering and giggling back from an all-night bender to crash out, all six of them, on the bed at nine o’clock in the morning. Poor old Don Pasquale meanwhile has just finished mowing his own lawn, namely the cross isle in the auditorium in front of the orchestra. He is weary and sweating, and breaks out a tinnie . . . tinnies are ubiquitous throughout the opera. In the front row, we are in the Forster’s foamy firing-line! The light and bright overture, suggesting the party, runs under all this, while suggesting things to come.

Don Pasquale, a frustrated sixty-something bachelor, is peed-off with his feckless nephew Ernesto, who will not marry for money, but is determined to hitch-up with his penniless but pulchritudinous girl-friend, Norina. He decides to teach Ernesto a lesson: he, Don Paquale, will himself marry and thereby disinherit his nephew. He has already asked his friend and family doctor, Dr Malatesta to find him a bride.

However, Dr Malatesta is also a friend and confidant of Ernesto and has hatched a plot to keep the lid on things. He will arrange a false marriage, ostensibly with his own sister “Sophronia”. And he has recruited Norina as Sophronia.

Don Pasquale is full of melodic invention and is rich with duets and quartets, bringing an interwoven musical profusion to the work. We hear wonderful parings of Pasquale and Malatesta and of Norina with all three male characters. The silver anniversary season has already showcased bass and baritone voices working with strength together in Macbeth and now in Don Pasquale, Doyle’s Pasquale with Cleverton’s Malatesta.

Acclaimed baritone James Cleverton makes a suavely subversive Doctor Malatesta. Hurried by an impatient Pasquale, he can’t help remarking to himself what a babbione (buffoon) he is, before reporting on his matchmaking. She is bella siccome un angelo ” as beautiful as an angel”, as Cleverton brilliantly invests the mellifluously sung description with an insincere sincerity, firing Pasquale with invigorated passion.

“A sudden fire” is Pasquale’s reaction, Ah! un foco insolito. The presto passage is an example, early in the action, of how acrobatic Grant Doyle can be with his bronzen bass voice as he forgets his ailments, begins to feel twenty again, and is imaging siring half a dozen healthy children by his new bride.

Spanish soprano Lorena Paz Nieto has made quite a niche at West Green House Opera playing coquettish roles with great verve and vigour. Her Norina is no exception; she plays the part of the feisty young woman, one self-assured and self-aware, with great panache. Norina is pert, precocious and provocative. (A costume coup, we catch a glimpse of her glittery g-string showing above her jeans.) She scoffs at the wiles of the women in the chick-lit she’s reading. Paz Nieto’s So anch’io la virtù magica has a naughty sparkle as she sings “I too know ways to capture hearts”. When Malatesta arrives and explains the plot, Norina’s resolve is strengthened as she has just read a note from Ernesto telling her he is too poor to be able to marry her. The duet between Malatesta and Norina as they rehearse the role of Sophronia is played full maximum humour.

The all-girls together scene is lit in pink by Sarah Dell whose lighting design subtly follows the action, and has great fun with it.

A short prelude for horn and trumpet (the trumpet being part of Jonathan Lyness’s orchestration) introduces a dejected Ernesto, betrayed as he sees it by his friend Malatesta, and having lost his true love Norina. He eats his heart out in his self-pitying aria Povero Ernesto! Colombian tenor Julian Henao Gonzalez makes an engaging empathetic Ernesto. In spite of a throat infection, Gonzalez doesn’t seem to mark his performance, and his glistening timbre has great appeal.

Sophronia, fresca uscita di convento, “fresh from the nunnery” plays her part as the shy sister, and when her veil is lifted, Don Pasquale is smitten. Misericordia, una bomba! “Strewth, what a bombshell!”. Lydia French’s surtitles cause much audience laughter with the translations from Italian to Strine. Donna becomes “Sheila”, mala becomes “crook”, all types of greeting become “G-day mate!”.

Studer and all the performers have a field day lacing the action with stacks of visual gags, some quite risqué . . . great fun has had with a sausage from the barbie!

Before the ink has even dried on the “marriage contract”, including an ill-advised article giving her the title of Lady of the House and full control over its finances, than Sophronia transmogrifies from shrinking violet to terrifying termagant. Rolfe’s costumes underline this change from demure ex-nun’s attire, to bridal gown with extra come-on features, to scarlet clad femme fatale as she determines to go out that evening sans new husband. It is a lepidopteran life-cycle in rapid reverse.

The scene whirls into an uproarious quartet she installs a baffled, but delighted Ernesto as her butler and ups the wages of the tre in tutto servants while calling for more to be employed. It is a Donizettian feast of song, hot off of the musical barbecue.

In the second half the Norina as Sophronia piles on the pressure for Don Pasquale. He is scanning the mounting bills and invoices and Doyle’s aria Che marea, che stordimento is brilliantly expressive of his dismay as he itemises the cost, not only to his pocket but to his pride. For by that evening she has become a vitriolic virago, and we hear the edge on her voice in Paz Nieto’s coloratura bite in their duet which leads to the climax of her striking him across the face, an act which elicited an audible gasp from the audience. Paz Nieto has top form when it comes to slapping.

The acting at this turning point in the opera is exemplary. Pasquale is crushed; and Doyle wrings out the pathos from his È finita, Don Pasquale, while Norina’s realisation the joke has gone too far is subtly expressed by Paz Nieto in her biting her lip out of sight.

Malatesta however continues the ruse in order to turn its direction. A letter has been planted ostensibly arranging a tryst between Sophorina and a lover. And what an opportunity this gives to showcase the voacla gymnastics of Doyle and Cleverton as Pasquale and Malatesta plan to thwart this assignation. Doyle’s Cheti, cheti , planning their silent entry into the garden to expose the lovers is countered by Clleverton’s Io direi… sentite un poco (“I’d say let’s listen a bit”) are both tumbling passages that lead in to a patter duet, so brilliantly, speedily and faultlessly executed that the response of the audience demanded a reprise.

In an entirely different mood, the meeting of Norina and Ernesto in the garden is beautifully lyrical. His Com’è gentil, “How soft . . .” is a typically Italian serenade and Gonzalez’s fluid tone is melodiously emotional. His ensuing duet with Paz Nieto, tornami a dir che m’ami, “turn to me to say you love me” has a heart-felt warmth. It is another different mood for Norina, and Paz Nieto expresses it with passion.

The eighteen-strong West Green House Orchestra, under the baton of Jonathan Lyness, plays with melodic grace and charm, but picks up the inherent knock-about nature of the piece. The is adapted score is Lyness’s reduced orchestration which has a liveliness and memorable hummability, without losing the vivacity yet veracity that Donizetti’s music has.

Is Don Pasquale about a silly old s** getting his comeuppance for being too mean, or about a gullible old man being being fleeced by greedy youngsters? Most productions tend towards the first interpretation, but Studer’s novel approach made one want to side with Pasquale, the conspiracy against him seeming almost too cruel.

But then again, humour arises from discomfort, and this Don Pasquale has comedy galore. This is opera buffa at its best. It is huge fun, and everyone involved comes away with big grins on their faces.

The moral of the story is explicitally mentioned in the final quartet and emsemble piece, each singer toasting with a tinnie of Forsters. Don’t marry in old age, it only brings you noise and pain with your trouble and strife.

Real good onya, West Green!

Mark Aspen, July 2025

Photography courtesy of WGHO

Trackbacks & Pingbacks