Messiah

Artistry For Advent

Messiah

by George Frideric Handel, libretto by Charles Jennens

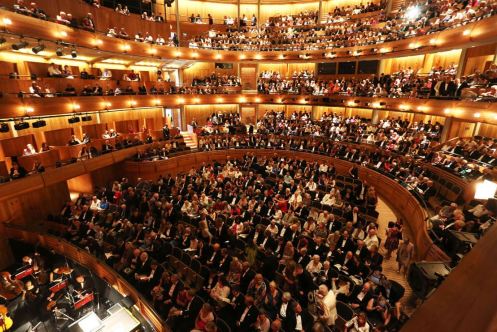

Glyndebourne Productions at Glyndebourne Festival Theatre until 14th December

Review by Mark Aspen

Advent Sunday this year is unwontedly sunny, so what could be more appropriate a day to see Glyndebourne’s Messiah, with its uplifting message of wonderful things to come. As a message even more needed in these present days when all news seems to teeter on despair, Messiah speaks loudly of hope, an advent of peace and redemption. Maybe this is why Handel’s masterpiece remains so enduringly popular and why even the most agnostic could not fail to be touched by it. Messiah has a powerful aura of hope and a sense of joy.

Joy is Handel’s musical stock-in-trade, that Baroque style that just bubbles along, and it is palpable in Glyndebourne’s heartwarming concert production. It is a resplendent mixture of urgency, contemplation and reflection. The sense of urgency was no doubt conceived by Handel’s manic impetus to create this massive and majestic work within an obsessive three and a half weeks of continuous labour. This production succeeds in just restraining that urgency enough to allow the poetry of the words and their meaning to be savoured.

The energy of Messiah occasionally gives rise to the concept of its staged presentation. The piece has a flexibility for this to be large-scale, as notably in Deborah Warner’s 2009 production with an impressive cast of actors, or more often as a smaller work with soloists also performing the chorus parts.

However, Messiah does not have a dramatic narrative. It is a conversation between the orchestra, the soloists and the chorus. Its three Parts concentrate on the significance respectively of the anticipation of a Messiah and his incarnation on Earth as the child Jesus; of the passion and resurrection; and of the second coming of Christ and the redemption of mankind. Jennens’ libretto is taken from the King James’s Bible of 1611 and the Psalms from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The chronology is quite fluid and it is full of cross-references, particularly in Part One where Old Testament prophecies, largely from Isaiah, are manifest in the Gospels. Effectively, these are 18th Century hyperlinks, but with soul. This conversation of cross referencing between orchestra and singers, and solo voices and chorus is something in which Glyndebourne excels. (It is a natural opera skill of course.)

There is a precision in presentation, and director Ian Rutherford clearly has an eye for detail. The two rows of chorus enter from opposite wings, but arrive in position at same time. They rise and sit as one. Minutiae perhaps, but it gives a neat and clean look. Imogen Clarke’s cyclorama lighting subtly and unobtrusively accompanies the mood of each section.

Without doubt, Messiah is famously known for its chorus pieces, and Handel certainly knew how to work them generously and to maximum effect. Aidan Oliver’s The Glyndebourne Chorus is in top form and it is exciting to hear how the sound ripples across the line. “All we like sheep have gone astray” sweeps thorough the chorus like a Mexican wave, musically replicating the animals’ straying. The chorus is clearly enjoying itself and all the voices are animated: “For Unto Us a Child is Born” sparkles with delight.

The four soloists’ accompagnatos and arias do not stand alone but form part of a lively dialogue between soloist and chorus. They come, however, often as surprise interjections. This is most noticeable in part one, the tenor declaration, “Comfort ye, my people”; or the bass with the assertion of the Lord of Hosts, “I will shake the heav’ns, the earth”. The opening soprano recitative, “There were shepherds abiding in the field”, although guileless and direct, has a rapturous elation. All elicit a response from the chorus that is confident and expansive.

This dialogue is marked in the opening words of the mezzo-soprano soloist, “But who may abide the day of his coming?”. Beth Taylor’s creamy and lush mezzo elaborates “for he is like a refiner’s fire”, delivered with an intensity that burns; and then develops into “thou that tellest good tidings to Zion”, singing with the chorus in a rhythm that bubbles and bounces along. As Part Two opens, Taylor excels in with the powerfully affecting aria, “He was despised and rejected”, velvet-voiced and full of emotional power.

Another touching passage is “I know that my redeemer liveth”, a soaring soprano aria. It has great emotional impact. Handel himself milked it in one performance by using a boy treble, an orphan from the Foundling Hospital, to sing the part. (Warner had Sophie Bevan lying in a hospital bed in the final stages of a terminal illness.) British-Iranian soprano Soraya Mafi sings the aria with exquisite poignancy, taking it to that aching pinnacle that heralds the chorus’s “Since by man came death” and that evolves into the crux of Messiah, mankind’s resdemption through Christ. Mafi’s lyric soprano has delicate coloratura expression in “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace”.

In the middle of this transcendental work, the notion of peace or rather the lack of it in today’s troubled world suddenly intrudes with rude reality. The soprano aria is almost immediately followed up by the punch of the bass aria, “Why do the nations so furiously rage together?” which has a huge impact in its delivery by James Platt, whose burnished resonant bass is matched by a monumental command of the stage. Handel has given the most portentous passages to the bass part, and Platt’s gravitas and driven delivery are superb in the accompagnato pronouncement “Behold, I tell you a mystery”, which leads directly into his aria, “The trumpet shall sound”, and thence into the final magnificent concluding passages of the work.

A word that occurs in the tenor passages is “scorn” and James Way interprets these with emotional depth. “All they that see him laugh him to scorn” and is countered with “He that dwelleth in heaven shall laugh them to scorn”. Recitative, but his aria that follows “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron” is delivered with emotional power and opens into the well-known Hallelujah Chorus. It is the tenor that has the hinge passages in this unfurling story of redemption, and he eloquently tells the message with a clarion elegance.

Aidan Oliver conducts The Glyndebourne Sinfonia and directs the The Glyndebourne Chorus with an integrated athleticism. All bring a controlled energy to the piece. The 32-strong Sinfonia, whose leader Richard Milone is a lively presence, canters gracefully. Continuo, Matthew Fletcher on harpsichord and Ben-San Lau on the chamber organ, are obviously an ubiquitous foundation, but most instruments get a chance to shine. The most striking is that Baroque speciality, the natural trumpet and, in a work that is as declamatory as Messiah, Simon Munday and Simon Gabriel make highlighted, and impressive, appearances.

All performers, instrumental and voice, comes together in the big set-piece moments. Hallelujah is the most famous, and is always an overwhelming moment. Equal, however, in its spirituality is the concluding Amen Chorus. Seemingly it is just 51 ways of slightly differently signing amen, but it has an entwined progression that thrills. In its simple complexity and complex simplicity, it is the final affirmation of this pre-eminent statement of faith; and as a work of art the Glyndebourne creation has beauty and depth.

On the title page of the libretto Jennens wrote “majora canamus”, quoting from a Virgil eclogue “let us sing of greater things”, and this production does that with consummate skill.

Mark Aspen, November 2025

Photography by Bill Knight and Sam Stephenson © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd.