The Yeomen of the Guard

Song to Sing

The Yeomen of the Guard

by Arthur Sullivan libretto by W.S. Gilbert

The Grange Festival, The Grange, Northington until 8th July

Review by Mark Aspen

Is there something Shakespearean about WS Gilbert’s libretto in The Yeomen of the Guard? There are changed identities, an improbable disguise, wooing by subterfuge, a philosophical fool and an ending involving three marriage proposals.

Is there something Wagnerian about Arthur Sullivan’s music in The Yeomen of the Guard? There are touches of grand opera rivalling Verdi, of symphonic style Mendelsohn-like passages, of the classical style of Mozart.

Yes to both these questions, but Sullivan also has folk song, shanties, dance music and musical acrobatics. All work seamlessly and congruently together. Gilbert has his trademark wit, patter songs, and satire (lightly touched.)

The Yeomen of the Guard pulls all these together with homogeneity. Nothing jars. It’s all very civilised, and very English. Yet, although it may be fun, there hovering under the surface is the dark shadow of reality. Hence, it is perhaps the most subtle of the G&S canon, and is widely regarded as their best collaboration.

The Grange Festival production respects, and indeed enhances, this subtlety without losing the joy of the genre, avoiding caricature without losing its sense of self-parody.

Gilbert and Sullivan had intended an Elizabethan setting, and an imminent beheading in the Tower of London. Director Christopher Luscombe relocates this most serious of comic operas to soon after the First World War, somewhere in the purlieus of the Tower. The impending beheading becomes a hanging that is pending (so to speak) … maybe it is less messy to stage. Why WW1 is not clear, but it does reinforce the concept of the hero worship of Colonel Fairfax, who is falsely imprisoned under capital sentence for espionage (rather than sorcery) and why Leonard Meryll, a junior army officer returning from the war, is so lauded for his acts of valour (or rather his alter ego is).

The set is the exterior of the domestic quarters within the Tower precincts, but no White Tower to be seen. Instead, designer Simon Higlett has the rows of half-timbered houses front a picturesque green. It is almost bucolic, except for the cannons on the sward. With the vibrant colours of the buildings and slight out-of-true lines, the effect hints at the best aspects of panto backdrops. All this with its liveliness and charm leavens the dark undertones of the plot.

Higlett also brings bright chocolate-box delight to the costumes, the saturated colours of the military and other uniforms, period-perfect; as are other details, including the hairstyles and ladies’ cloche hats and dresses. Paul Pyant’s lighting design enhances this Golden Age ambience.

The set is a gift for Tom Primrose’s two dozen strong Grange Festival Chorus, who have a busy time is this performance. There is a unity about the ladies’ chorus’s set piece entrances. They nip out of their front doors as one, whether from nervousness or from joy, or whatever other the impetus takes them. Ditto, the men’s chorus who in contrast march in, resplendent in their Yeomen’s uniforms, brave veterans “suckled on gunpowder”. This cohesive integration of set, chorus and music enriches the confident style of Sullivan’s score.

The core of the plot is Fairfax’s forthcoming execution, from which he is sprung disguised as Leonard Meryll, who is the son of the Sergeant of the Yeomen. Fairfax has been framed by his evil cousin, who will inherit his estate. If he were to have a wife, he could thwart his cousin, so he is determined to be married in the few hours before he is hanged … to any available woman. All the usual Gilbertian shenanigans ensue.

Nick Pritchard’s Fairfax is a recognisable confident ex-public-school officer, with a natural charm. Pritchard, no stranger to The Grange, sings with easy articulate appeal, his soft tenor’s expressiveness exemplified in the reflective ballad “Is life a boon?” with its poignant message “Death, whene’er he call, must call too soon”.

Fairfax is admired by all. All the military men seem to have fought with or for him. These include the Governor of the Tower, Sir Richard Cholmondeley, played with commanding presence by baritone John Savournin, and Graeme Broadbent’s morose Sergeant Meryll. These singers are consummate and prolific G&S singers; in Broadbent’s case, his rich bass voice has been heard in 146 different operatic roles.

Fairfax is admired in a different sense by Phoebe Meryll, the Sergeant’s daughter. Although she tries to keep it secret, she can’t resist using her attraction for Fairfax to tantalise the chief gaoler Wilfrid Shadbolt, who has been ardently pursuing her. Mezzo-soprano Angela Simkin, whom we last saw at The Grange in Falstaff, makes a captivatingly coquettish Pheobe, lovelorn in her desire for Fairfax in the opening aria “When maiden loves, she sits and sighs”, then mischievously teasing Shadbolt with “Were I thy bride”, and bringing out the best of Sullivan’s lilting score in both these contrasting pieces. Nicholas Crawley’s rough-edged Shadbolt, adds a hoarseness to colour his bass-baritone and display the jagged jealousy in Shadbolt’s character. It must be said that both Simkin and Crawley are actors with insight, expertly expressing the emotions of their characters, witness the final scene when Fairfax’s intentions are unravelled and Phoebe contents herself with becoming Mrs Shadbolt, albeit with a second-best groom.

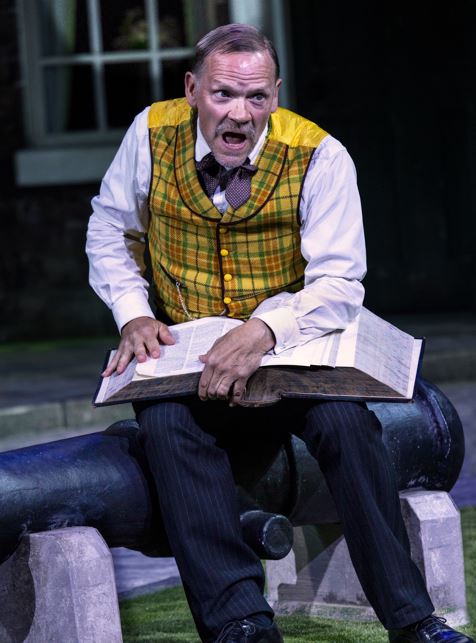

Fairfax’s unwittingly prospective bride, and widow, suddenly makes an arresting appearance as a travelling showman’s motor wagon arrives noisily on Tower Green surrounded by a hard-to-please would-be audience. The travelling showman is Jack Point with his partner in a comedy duo, Elsie Maynard. To quell the crowd, they perform The Merryman and his Maid, a song that echoes the plot of the main story … but not quite. This duet, “I have a song to sing, O!” has become a G&S favourite and is the ear-worm of this opera. It is a welcome ear-worm though when sung as enticingly as by the contrasting voices of Ellie Laugharne as Elsie and Nick Haverson as Jack. A highly-sought performer on the opera stage, Laugharne is equally at home with all opera genres. As Elsie she sings with the power of grand opera and the lightness demanded by operetta, her limpid soprano an absolute delight to listen to. Haverson sings with a light bass textured with a gravelly timbre, underlining the character.

When Elsie is led back blindfolded from her contracted marriage, destined to last under an hour, her reflective aria “’Tis done, I am a bride” is sung by Laugharne with truly touching compassion. However Fairfax has escaped disguised as the newly appointed Yeoman, Leonard, played with great sincerity by the fine tenor David Webb. The complications that ensue are resolved much to Elsie’s favour, but an accidental love triangle has been created, since Jack has dreams to marry the younger Elsie, a comfort to his retirement.

Nick Haverson’s Jack is a fading old stager from the music-hall and from its East End home. He is quick witted and indeed well-read, his puns are almost Shakespearean and he does quote directly from the Bard, but his tumbling tongue-twisters and patter spiral from him with practiced ease. Haverson is a consummate actor with the flexible physicality of a contortionist. It is difficult to say which is the most nimble, his verbal agility with Gilbert’s text and patter-songs, or his agile acrobatic movements that melt into the music. He almost steals the show above the singing, and certainly was well received by the audience, in spite of the reservations of some G&S purists, as some of his songs were cut.

The execution does not take place, but the subterfuge is blown by the astute spying of the housekeeper of the Tower, Dame Carruthers and her niece Kate (Caroline Taylor). Carruthers has worn her heart on her sleeve for Sergeant Meryll, and now has some leverage to move him. Mezzo-soprano Heather Shipp has great fun as a mischievous Carruthers.

There is however, something troubling about Gilbert’s plot. The denouement produces three couples who are betrothed by coercion. Fairfax has married Elsie by deception, Sergeant Meryll is betrothed to Dame Carruthers to buy her silence, and likewise Phoebe and Shadbolt are having a “long engagement” to cover up Phoebe’s involvement in the conspiracy to spring Fairfax, despite Shadbolt lying about shooting Fairfax dead, a ruse to clear the ground for Jack to regain Elsie. What a complicated web we weave …

This particular complicated web is given voice in the powerful “Oh, day of terror!” which builds to a septet and a full choral piece, which rivals Verdi or Wagner at their most magnificent. It may be spoof sentiment, but it certainly packs a punch in this production. But The Grange Festival’s The Yeomen of the Guard has full-on verve and stacks of energy. An example of the dynamism is Ewan Jones’ choreography, manifest for instance in a dance duet with Jack and Shadbolt, “Tell a tale of cock and bull”.

John Andrews conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra with crystal-clear, inspired vitality, eliciting the versatile mastery of Sullivan’s score, in a scintillating performance.

So yes, Sullivan’s music has the grandeur of his contemporary composers in this, one of his most ambitious scores, as Andrews demonstrates.

Is there something Shakespearean about Gilbert’s libretto? The words smack of Shakespeare’s, but Luscombe’s production highlights the role of the fool. There are King Lear’s Fool, Feste, Grumio, Dogberry, Touchstone or Autolycus. These are complex characters, a bit like a Greek chorus, commenting on the action, but they offer philosophical pointers, and are redemptive lightning-rods for the emotions of the principals. In The Yeomen of the Guard, Jack Point takes the role of a Shakespearean fool, as Haverson’s portrayal points up. Jack is a complex character, who reflects the main themes. His The Merryman and his Maid mirrors the story if it were to have a happy ending for Jack. In his reprise of the song in the final scene, he tellingly does not sing the last two stanzas

However, what is certainly un-Shakespearean is to finish a comedy with a tragic coda. Somehow, it makes of a better story. Jack is not a Shakespearean fool, he is more like Rigoletto, a tragic and flawed human being, distressed, distraught, bereft.

… he sighed for the love of a ladye!

Mark Aspen, July 2022

Photography by Simon Annand

Trackbacks & Pingbacks