Alex Ingram, Alex White, Andrew May, Anna Marmion, Anne Brontë, Ashley Martin-Davis, Biraj Barkakaty, Branwell Brontë, Charlotte Brontë, Charlotte Hoather, Elena Garrido Madrona, Emily Brontë, family, Grace Nyandoro, Jane Eyre, Katharina Kastening, Lisa Logan, Magdalena Mannion, Martin Lamb, Polly Teale, psychological drama, relationships, sex, violence

Brontë

Moor and More

Brontë, the Opera

by Lisa Logan, libretto based on the play by Polly Teale

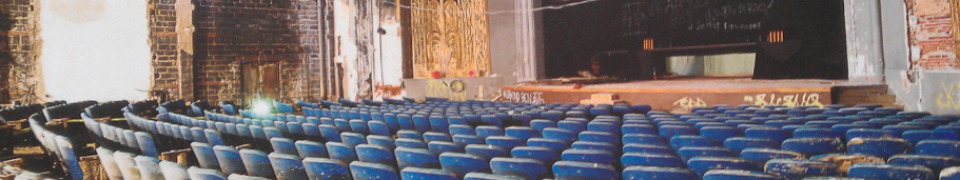

Keynote Opera at the Arcola Theatre, part of the Grimeborn Festival, until 16th September

Review by Mark Aspen

Forget the windswept moors, the Yorkshire accents, the lumpen servants carrying lanthorns in the dark, for the Brontë sisters in Lisa Logan’s new opera inhabit another wild darkness, a Freudian world of their own psyches. The foreboding heathland is condensed into their father’s parsonage, where they are confined by the mores of the early Nineteenth Century.

It is perhaps therefore pertinent that the world première of Brontë, the Opera should take place in the Arcola Theatre, whose snug acting space emulates the claustrophobic ambience of Haworth rectory.

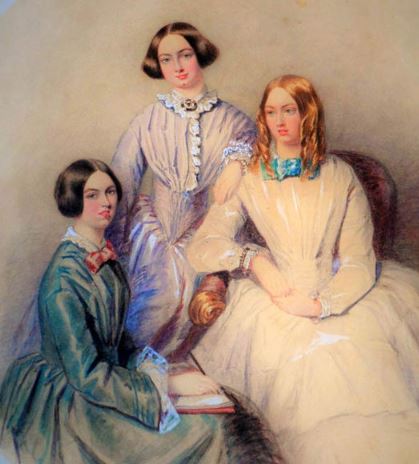

Charlotte, Emily and Anne are trapped with their own longings, for freedom, for love, for independence; trapped by social standing, by religious convention and by perceived propriety as women. Their inner escape is manifest via the twins of fantasy and poetry, forms of self-expression that were to blossom into some of the English language’s finest literature.

The psychology explored in Brontë, however, is the relationships between the creators and the created. How much are the fictional characters that each creates biographical manifestations of themselves? How much do the plots of their novels and the themes of their poems reflect their own hidden desires? Hence Jane Eyre, Cathy and Nelly occupy the stage to disconcert their creators, as do Rochester and Heathcliff; all and each an ominous disquieting presence.

The opera is full of symbolism. Birds, and particular their tissues that are most expressive of freedom, their feathers, have an ubiquity. Their father, the Rev’d Patrick Brontë, is mostly blindfolded, as if (wanting to be) unaware of the secular activities within his own household. Sheets of foolscap paper dangle from the flies, indicative of the sisters’ overarching preoccupations … and they resemble birds.

Designer Ashley Martin-Davis’ set is otherwise remarkably simple, a doorframe with a heavy door, and a robust rustic table, which can also do service as a bed, a fantasy ship, a locked room, or a number of abstract framings. The costumes are eclectic. Period tends to be hinted at, rather than literal. Modern trouser braces support period breeches while period dresses are underpinned with modern foundations. Charlotte wears trousers, perhaps symbolic of her link to modern thinking. Inspired though, is the coding of fictional characters with the script of “their” novel longitudinally handwritten on white bodices or waistcoats.

Musically, the sisters are often presented as a whole, witness an early trio setting the scene, Beyond the House is a Moor, a beautifully integrated piece. However, the Brontë siblings did not bond equally. Setting aside the eldest of the siblings, Maria and Elizabeth, who died in childhood and do not feature in the opera, Charlotte was closer to Branwell, their only brother, whilst Emily and Anne supported each other into adulthood.

Charlotte, the eldest, tended to seek to control the others as adults, and this domineering nature is portrayed by Spanish soprano Elena Garrido Madrona in the role. She has a musically dramatic entrance, percussive and thrusting, preparing the way for the alpha sibling. Madrona makes a strong Charlotte, immersed in the character as we follow her journey of personal discovery and its tribulations. It is a demanding role vocally, as are almost all of the parts in Brontë , which she expounds with a tireless expressive vigour.

Charlotte’s own creation, Jane Eyre, is seen as her alter ego, skilfully differentiated by Madrona.

Equally impressive as her sisters are sopranos Anna Marmion as Emily and Grace Nyandoro as Anne. Marmion depicts Emily as shy but acutely aware, an observant naturalist who opens the duet Beautiful Bird, imbued it with effectively decorated trills. She also has some lovely held notes in the adagio passage in Emily’s death scene. Nyandoro’s Anne is a gentle creature, concerned and caring, and she adds a lyrical softness to her arias, such as This Time Tomorrow as she leaves to be a governess, and A Woman Who Is Married.

If Emily and Anne tend to calm things down, it is Charlotte and Branwell who stir things up.

Charlotte and Branwell are seen as children playing fantasy games, and Branwell’s favourite is sailing a boat (the table inverted) in a battle, especially as he insists on being its captain. However, in adult life it is he who rocks the boat of the gentility of the Haworth parsonage. A trip to London to present his paintings at the Academy is marked with excitement and excessive expectations of life in the city, with a quartet of Mozartian complexity by all four siblings. In the event, it is disastrous. Branwell alleges that he was robbed of his money, but it seems likely that failure in his quest leads him to blow all in a spree of drunkenness and dissolution. It is Branwell who drives the plot, and makes Brontë an opera of Gothic tragedy.

Alex White excels as Branwell, his strong tenor voice bolstering the personality of the Brontë brother, and accurately charting his descent into alcoholism and mental instability. His decline is most shockingly accented when he attempts to sexually assault his sister Charlotte. White has busy stage time, as he doubles convincingly as the fictional characters Heathcliff and Huntington (from Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall), Gothic heroes, whose temperament is inspired by Branwell’s.

Within Brontë, the Opera, these and other fictional characters are omnipresent, allegories for their creators own stifled frustrations and repressions. Cathy from Wuthering Heights particularly preoccupies Emily’s thoughts. She is portrayed as a wan, willowy presence, an otherworldly literary spirit, by Charlotte Hoather, whose ethereal soprano beautifully interpolates into duets with Marmion, both as Emily and as Wuthering Heights’ Nelly.

Rochester, the towering presence in Jane Eyre and Jane’s thwarted bridegroom, is played in a doubling role by Martin Lamb, whose main real-life character is the Rev’d Patrick Brontë, patriarch of the family. An established performer, Lamb’s rich bass-baritone lends an air of authority to the mirrored roles of Brontë and Rochester. He also plays Héger, the Belgian schoolmaster, to whom Charlotte became deeply, and unrequitedly, attached. Giving these three roles to one performer pointedly underlines the confused emotional state of Charlotte.

Rocking the psychological boat is the presence of Bertha, the deranged and confined wife of Rochester. She is played by a skilled dancer, who is seldom not onstage with Charlotte. Bertha is a figure invoking mixed emotions of repulsion and sympathy, of awe and pathos, of fear and attraction. Spanish dancer Magdalena Mannion choreographs her own plot to great effect, in a wild exuberant style, constantly in agitation, energetic and expressive. Her style has elements of flamenco, and it was not surprising to later discover that Mannion holds a master’s degree in Flamencología. (It was more surprising to find out, in pure ignorance, that there was such a discipline as Flamencology.)

There is no doubt about the skills of Keynote Opera’s performers as actors, singers and dancers, but they could be somewhat better served by the libretto, or rather the play from which it is derived. It is an unremitting tragedy, overhung with Gothic gloomth, and as such is on one emotional level, with nowhere from the performers to come from or go to. And it is nearly three hours long (including the interval). More dimension, more light-and-shade would make a more satisfying plot.

That said, the work is leavened by one character who provides some light relief, Mr Bell-Nicholls, Rev’d Brontë’s curate. When he is first seen, knocking timidly on the parsonage door, to introduce himself in an awkward meeting with the three sisters, he is a figure of fun. In the course of time he is to ask for Charlotte’s hand in marriage, from her rather incredulous father, and she was 38 years old when she finally accepted. It is only after her (tragically short) marriage that we see Charlotte begin smile, lovingly at Arthur Bell-Nicholls. Biraj Barkakaty gets the part of Bell-Nicholls spot on, effete at first, then growing in confidence, and finally the happily married man. The role is a great countertenor part, but sadly all too small a role, for Barkakaty has a fine singing voice.

Oh, there is one other time when Charlotte smiles, when she has the approval of the newly published Jane Eyre from her strait-laced father, who had hitherto not known of its existence.

Lisa Logan’s score is a remarkable musical tour de force, intricate, mesmerising and absorbing. Atonal in nature, it smacks a little of Alban Berg. It has lyrical moments, such as Emily’s death scene, and there are many descriptive passages, particularly of birds. It is scored for wide range of instruments, including a celeste. However, it does lack a little in variety, perhaps constrained by the lowered dimensions of the playscript.

Nevertheless, conductor Alex Ingram has taken the score to his heart and has the whole piece in controlled and experienced hands. Ingram is an acclaimed conductor of both opera and ballet works and it shows in his concentrated and focussed steering of the work. He has a dedicated orchestra in the twenty-strong Docklands Sinfonia, and their contemplative attention to the piece is palpable.

Amazingly, the opening press night is the first time that the opera has been staged with orchestra. One must admire the bravery of Keynote Opera, but they have certainly pulled it off well.

The whole undertaking of a premièring such an involved work with limited resources and theatre space is highly ambitious and director Katharina Kastening has achieved a remarkably successful production that deserves wider acclamation.

Keynote Opera’s production is a dark psychological treatise probing the innermost feelings of literature’s most famous three sisters, their loves and hates, their fears and desires, their successes and failures. In their attempts to build or undermine each other, oxymoronically they are in a supportive rivalry, while the frustrations of the stiffing effect of the mores of the time bring forth literary immortality post their tragic early loss.

Brontë, the Opera is a work of art emerging from its confines, ready for wider vistas.

Mark Aspen, September 2023

Photography courtesy of JP Humbert; sound clips courtesy of Keynote Opera

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Rating: 4 out of 5.From → Arcola Theatre, Keynote Opera, Opera

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thanks so much for such a detailed, kind and supportive review of the whole team and thanks for your time, best wishes Lisa

It was a pleasure to review an engaging and intriguing new opera. Congratulations on a magnificent score