The Father

Nature’s Hand Dealt

The Father

by Florian Zeller

Rhinoceros Theatre Company, at the Coward Studio, Hampton Hill Theatre until 20th January

Review by Gill Martin

A momentary murmur of confusion shivers around the audience. We are suddenly plunged into the depths of doubt and uncertainty that plague the minds of those with Alzheimer’s -and those closest to them.

Welcome to the world of André, an engineer who might have been a tap dancer … or a conjurer. His broken mind conjures a myriad of events both real and imagined, pleasant and painful, terrifying and menacing.

By confusing the characters and changing the set we, as an audience, are both mystified, tortured and even amused as André tries in a muddled timeline to untangle his brain.

The Father is a tragi-comedy brought to the cinema in 2021, and brought to life with stellar performances by Anthony Hopkins in the title role and with Olivia Colman as his patient, put-upon daughter, wrestling guilt and duty, always aware she was the less favourite child.

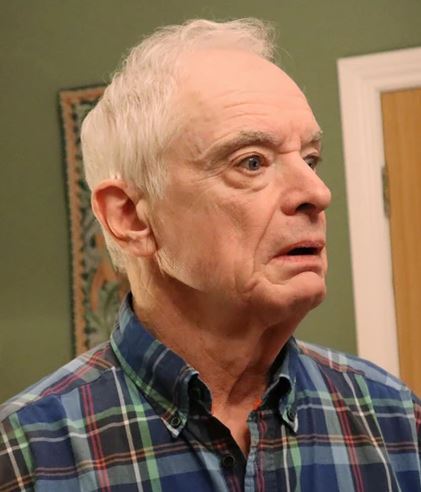

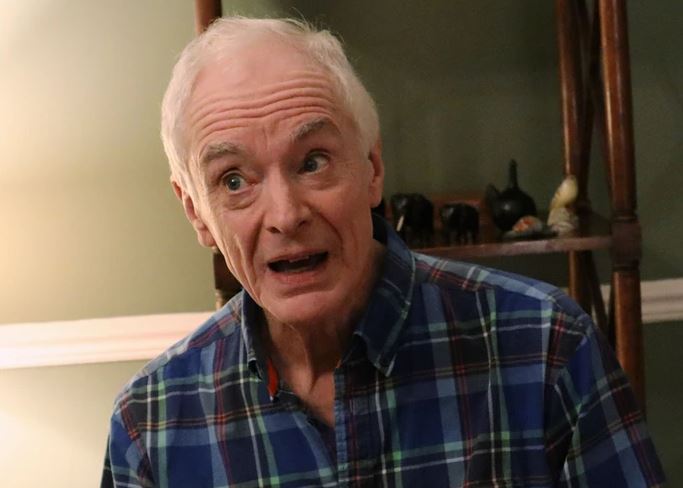

Nigel Andrews takes on the main role with assurance. At 76 and white haired, he is easily believable as an 80 year old, charming and roguish one minute, then querulous and demanding the next, smart in brown casuals, vulnerable in polka dot pyjamas, perplexed as he is moved from his comfortably cluttered flat, to the ‘horrible minimalist’ apartment of his daughter and her partner, to his stark white bed and attending nurse.

We take his journey with him, accompanied by the strains of mournful cello music, and by the characters who punctuate his existence: daughter Anne (Denise Rocard); her partner Pierre (Oliver Tims); chirpy carer Laura (Helen Geldert); The Man (John Wilkinson); The Woman (Danielle Thompson). Some are interchangeable, adding to our confusion. All are well able to tackle this demanding performance at Hampton Hill Theatre’s Coward Studio.

We want to sympathise with André’s distress in his obsession over his ever missing wristwatch, his fear of being manipulated then dispatched to a nursing home. He morphs from cantankerous and masterful into blubbing for a lullaby. His behaviour both amuses and infuriates, sparking such lines as: ‘if this goes on he’ll be stark naked and won’t even know what time it is;’ or ‘how much longer must you stay around and get on everyone’s tits?’ Anne even has a nightmare about choking him in his sleep.

Director Fiona Smith explains her responsibility to portray the progressive, incurable condition that afflicts around 900,000 in the UK alone. She says: ‘The arts have always sought to allow us into the minds of others. However, this condition make understanding terrifyingly impenetrable. If our minds are the seat of our identity, this illness impacts our thinking about identity itself. If we are not “ourselves” then what are we? It appears a particularly cruel violation, pushing the limits of love and patience of the human we know’.

‘The Father is subtitled ‘a tragic farce’. The humour is bleak but still present. We see all events from the perspective of André, an eighty year-old man. We share his uncertainty of the shifting events in the play. To André, everything has become absolutely ludicrous. The miscommunication and absurdity he experiences are reminiscent of farce.

‘We have no reliable narrator, no coherent or chronological progression of events. Does the action take place in André’s flat or at his daughter Anne’s home? Why is all the furniture disappearing? Is Anne leaving to live in London or staying with him? Where is his other beloved daughter Elise? Time is no longer a stable reality. Scenes are replayed in alternative settings by different actors playing the same character.

‘We too, are at a loss as to what to believe.’

French playwright Florian Zeller’s multi-accolade winning The Father premiered in Paris in 2012. The English translation by Christopher Hampton, later transferred to UK theatres before Zeller wrote and directed the film, for which Hopkins took the Academy Award for best actor.

Actor Nigel Andrews embraces this rare ‘old’ role as ‘an unbelievable gift.’ ‘What a gift – again – for an older actor,’ he writes. ‘So little security. And yet so much excitement in unlocking this chaotic treasure house of an old man’s mind. It’s a mind that has lost nothing in quantity of memories and thoughts and insights. All he’s lost is the map to this Aladdin’s cave, and with it the understanding of where everything is, what everything is – and why everything is.’

‘We the audience, are all playing a kind of blind poker.’

To which we might add: And we, the audience, don’t yet know what hand we have been dealt.

Gill Martin, January 2024

Photography by Anastasia

Trackbacks & Pingbacks