The Circle

Double or Quits?

The Circle

by W Somerset Maugham

Theatre Royal Bath Productions and the Orange Tree at Richmond Theatre until 24th February

Review by Mark Aspen

Do we learn from history? No, of course not. Can we learn from family history? Well, um, perhaps not. This second question is the premise of Somerset Maugham’s The Circle, written in 1921 in the reactionary aftermath of the Great War.

The term “dated” is annoying often applied to plays whose characters do not conform to today’s mores, which usually misses the point that these are works with much to teach today’s world. (Is Shakespeare dated? Is Aristophanes?) There is certainly much for today to learn in The Circle, including the inestimable value of marriage (from an author whose own short-lived marriage was almost a façade), and the multifarious emotions disguised in the word love.

The Circle, however, is a comedy, and embraces these subjects with a light touch. It is written with quicksilver wit, sparkling and fresh. Indeed the whole script seems a concatenation of sharp aphorisms. Director Tom Littler puts Maugham chronologically in a “golden thread” of writers between Oscar Wilde and Nöel Coward. Arguable Maugham is superior to both, and the talented cast hone a sharp edge to his text.

It is the summer of 1920. In the grand Dorset country house of thirty-something Arnold Champion-Cheney, MP and his young wife, Elizabeth, an awkwardly interesting luncheon party is about to take place. The over-romantic Elizabeth has invited his mother Lady Catherine, known widely as Kitty, to come down from London, where she is on a trip from her home in Florence. The problem is Arnold has not seen his mother for thirty years when she ran off with her lover, Hughie, Lord Porteus … who is coming with her. As a further complication, Arnold’s father, Clive Champion-Cheney has just unexpectedly arrived too. Oh … and then there’s the young and dashing Teddie Luton, a planter from the FMS (the Federated Malay States) and friend of the couple, who is also down for the weekend.

The situation could be quite combustible, but the older protagonists are mature enough to accept it; almost. However, it holds a potency for the younger characters.

Louie Whitemore’s design comments on the situation with clever subtlety. The Regency style room has elegant proportions, and superb craftsmanship in its joinery of fielded French doors and six-over-six double-sash windows. Arnold is fastidiously obsessed with interior décor and particularly period furniture. The windows and doors float, hanging unattached to any structural elements, rather like the marriages in the plot, having appearance but lacking substance. Ironically, the un-joined joinery is dazzling white, pure, quite unlike the family relationships. Exits and entrances can be made without heed for the structure. The symbolism extends to the period pointed costumes: Porteus wears “co-respondent’s” shoes.

Free-thinking Elizabeth has a wide-eyed innocence that barely conceals her romantic excitement at her mother-in-law’s audacious amorous adventures three decades earlier Elizabeth fantasises her notions about her. “Some of us are more mother; some of us more woman”, she breathlessly states. Olivia Vinall scintillates as Elizabeth, bright, bubbly and flirtatious.

If opposites attract, Arnold would be an ideal husband for Elizabeth. He is dour, serious and grounded in his calling to politics. Propriety is all for the buttoned-up Arnold. When cornered emotionally, he retreats into studying his newly acquired Sheraton chair and the provenance of its legs: its neoclassical English style is a metaphor for Arnold. Yet, inwardly he bears the scars of his mother’s abandonment of him, aged five. Arnold and his marriage are in fact quite fragile. Pete Ashmore has Arnold’ stiff upper lip approach down to a tee, portraying both his intransigence and his bottled frustrations.

The unanticipated appearance of Arnold’s father, whom they thought to be staying in Paris, is disconcerting. Arnold appears harassed, but Elizabeth and her father-in-law are in many ways on the same wavelength in outlook and she welcome the extra layer of intrigue his presence might bring.

Clive Champion-Cheney is witty, erudite, but mischievous. Clive Francis plays Champion-Cheney senior with an air of jaunty insouciance and constant twinkle in his eye. His character gets the wittiest of the lines and Francis delivers them with amused satisfaction and well-timed punch. Champion-Cheney, unlike his son, has largely healed in his feelings towards his one-time wife and, on meeting her and her erstwhile lover, can greet them with almost friendly equanimity while, as an entertained observer, he can contemplate what they have become.

And what have they become? Both have lost their place in society and their aspirations, Kitty as a socialite and renowned beauty and Lord Porteus as a putative Prime Minister. Both Lord Porteus and Clive Champion-Cheney were eminent cabinet level politicians, but the scandal of Kitty’s absconding has left their ambitions thwarted.

When she arrives, Kitty is discovered to be a brash over-decorated woman of adamantine self-assurance, clinging onto her perceived youth. She is not the picture that Elizabeth had painted in her mind. Nevertheless the two women rapidly warm to each other. Both exude confidence, both are adventurous risk-takers, both are redheads. Jane Asher burrows gimlet-like into the character of Kitty. She has said of the role of Kitty, “She’s a fascinating character and joy to play”. That joyousness comes across in her portrayal. An aging woman growing old disgracefully could be caricatured, but Asher gives her real depth. In a touching scene, she weeps when confronted with photographs of her own beauty in her youth.

Porteus has become prickly and irascible, a man whose patience has been frayed by unfulfilled aspirations. He has become the grumpy old man par excellence, jaded and exhausted. Nicholas Le Prevost rather revels in the role, often using just body language or a grunt or shrug to raise a laugh. Yet he too imbues the part with depth, and the mutual affection, in spite of themselves, between Hughie and Kitty shines through the bickering. They have become accustomed to each other, a habit; maybe a bad habit.

Clive Champion-Cheney’s attitude to Lord Porteous is courteous, tolerant, almost friendly. It rather wrong-foots Porteous, making him even more tetchy. Even the occasional barbs are silken edged. There is a very humorous scene when Clive and, to a lesser extent, Kitty goad Porteous by interrupting his bridge game. The acting of the edgy comic timing is very cleverly done.

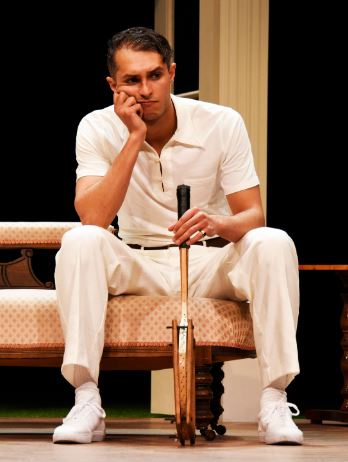

In the heady atmosphere engendered in Elizabeth’s mind by the renegade lovers of yesteryear, her burgeoning attraction to the handsome, relaxed and unencumbered Teddie Luton escalates. His presence is a seductive stimulant for history to repeat the three decades past adventures of her mother-in-law. A moment’s surrender is seen in a gaze held fractionally too long. Daniel Burke plays Teddie with an urbane charm. If Teddie’s a cad he’s an unguent one.

When Arnold realises his wife’s incipient infidelity, his upper lip becomes distinctly un-stiff. His reaction seems at first a little puerile, but in a touching scene, brilliantly acted by Ashmore, he unbuttons his true feelings of love for Elizabeth.

Will the circle come round and family history repeat itself? This is a balance that tips one way and another between the crux and the denouement of the play.

Murray, Arnold’s butler, unflappable and just as fastidious as his master, is rather like a one-man Greek chorus, subtly commenting on the action; in the hands of Robert Maskell in the role, by the slightest lifting of an eyebrow of a brief sideways glance.

Littler has been painstaking in his directorial detail to create a precise and stylish work. The detail in Whitemore’s design is enhanced by the crisp lighting of Chris McDonnell. When entrances and exits are not concealed by the set, then the lighting targets have to be very clearly defined. Equally, Max Pappenheim’s sound design has a subtlety. His birdsong, for instance, has a subliminal quality, occasional trills, quiet; rather than a repetitive loop of the same avian song.

There is an uncanny prescience in Maugham’s play. The plot in many ways foreshadows the events of fifteen years after its writing, in the abdication crisis of King Edward VIII. Moreover, the mores of the 21st Century, as either lax or liberal, according to one’s viewpoint, are predicted with acumen.

What is learnt from history? Tom Littler’s production of The Circle leaves the answer a little more ambiguous than Maugham’s script, but the nature of circles is that they tend to close, and the circle rolls on.

Mark Aspen, February 2024

Photography by Nobby Clark and Ellie Kurttz

Trackbacks & Pingbacks