Turn of the Screw

A Twist of the Knife

Turn of the Screw

by Benjamin Britten, libretto by Myfanwy Piper

English National Opera at the London Coliseum until 31st October

Review by Patrick Shorrock

This magnificent performance shows that English National Opera are still very much firing on all cylinders. It may require an orchestra of only thirteen players, but the varied colours and sheer tension conjured up by Duncan Ward and the ENO orchestra don’t feel in any way small scale, even in the vast space of the Coliseum. Every turn of the musical screw and twist of the dramatic knife is beautifully realised, arising naturally from the music rather than being imposed on the score. The audience, including plenty of under-21s, is completely sucked into the Britten’s vortex of operatic tension. There is that sense of a whole house completely enthralled that only comes with the finest performances.

Late in Britten’s career and premiered in 1954 – seventy years ago –Turn of the Screw plugs into that very contemporary subject, child abuse. But it is set in a pre-safeguarding era where the vocabulary to describe abuse doesn’t really exist. There is a school of thought that the real abuser here is the Governess who uses the children, Miles and Flora, to indulge her own neurotic fantasies, as her obsession with the recently deceased Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, the Governess’s predecessor, takes hold. That kind of thinking seems rather sexist and dated today where there is rightly a default position of taking safeguarding concerns seriously.

Director and designer, Isabella Bywater sets her production in a psychiatric ward, where the Governess relives her traumatic experience at Bly, the isolated country house where she was in charge of the children, with an absent guardian and only a housekeeper for adult company. There is no suggestion that what we see is only a fantasy of the Governess – after all the opera gives Quint and Jessel their own voices and they are visible even when the governess is absent. Bywater makes it clear – not just in her production but in a programme note – that ‘even if the ghosts are not real, there was something very much amiss at Bly’. It is left ambiguous whether the governess has been locked up as someone dangerous and a scapegoat for Miles’s death or has been utterly traumatised by her experience.

This is a brilliant production concept, although it is not always executed with quite the clarity that it requires. It starts well with the prologue (sung with melting beauty by Alan Oke) narrated by a doctor in a white coat sharing details of a case with a nurse. Bywater’s set is stunning: blank white walls with a couple of windows and an additional wall that moves in front and allows for changes with the furniture. Above are stark, bare branches, beautifully lit by Paul Anderson. During the interludes, black and white images (made by Jon Driscoll) of a huge stately house, the garden, the neighbouring church, and a wood are projected onto the walls. The projections glide in a way that makes the whole set appear to move and they work superbly well, especially when they indicate Miles’s point of view as he walks down the stairs to meet Quint outside.

But we are often left unhelpfully muddled about whether a scene is taking place in Bly or the psychiatric ward, whether it is a hallucination or a genuine recollection, which leaves the audience somewhat at sea. The Governess seems to get into her own bed on the psychiatric ward – which is next to a bed also occupied by a patient, as a nurse is glimpsed walking down the corridor – only to have to get up again and start talking with the children. This muddle might be the result of very careful thinking, and intended to intensify the sense of unease, but it is often the source of confusion rather than constructive ambiguity.

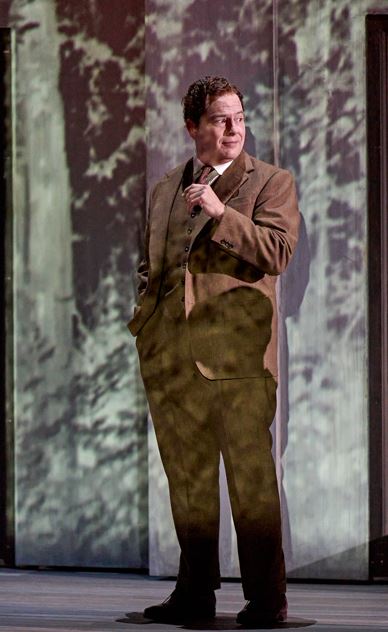

The performances are all good and Ailish Tynan’s Governess and Alan Oke’s prologue are outstanding. They make Britten’s angular vocal lines into things of beauty, which is all too rare. Tynan avoids febrile neuroticism but effectively conveys the distress of a mind adrift and overwhelmed by her situation. Gwyneth Ann Rand as Mrs Grose delivers in an unrewarding part. Louth and Victoria Nekhaenko are a couple of deliberately rather blank children who don’t reveal anything, which is more disturbing than fake malevolence. Bywater makes their games look distinctly sinister – there is clearly something nasty going on, but we are not allowed to see what. Robert Murray – good but without Oke’s sheer beauty of tone – drifts around malevolently, sometimes in a brown coat, sometimes in valet gear, sometimes in a dressing gown, sometimes pushing a tin trolley. Eleanor Dennis as Jessel has frustratingly little to sing and left you wanting to know more, as well as suggesting that she was possibly as much a victim of Quint as the children and the Governess.

I have not always been a fan of this particular opera, but this performance demonstrates that it deserves its place in the Britten canon and I came away with a renewed respect for it.

Patrick Shorrock, October 2024

Photography by Manuel Harlan

Trackbacks & Pingbacks