Nutcracker in Havana

Nut Shatter

Carlos Acosta’s Nutcracker in Havana

by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, arranged by Pepe Gavilondo Peón, further augmented by Yasel Muñoz

Norwich Theatre and Valid Productions for Acosta Danza at Richmond Theatre until 27th November, then on tour until 28th January

Review by Mark Aspen

A December outing to the see much-loved Nutcracker is much a part of Christmas as mince pies and brandy butter. White tutu-ed ballerinas, white snow, Sugar Plum fairies all spring to mind, and the sounds of a full orchestra’s soaring but hummable music are Christmas ear-worms. That’s Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, yes?

Now, bring in that doyen of the ballet world, Carlos Acosta CBE, matured in The Royal Ballet, and one can expect a superb chocolate-box traditional ballet, yes?

NO! Carlos Acosta brings in his native Cuba to the confection, where waltzes can dissolve into congas, ballet shoes can be over-shod with wooden flip-flops, and those soaring strings play alongside claves and saxophones. The purist might expect a mash-up.

The purist would be wrong, but would be delighted he was wrong. For Carlos Acosta’s Nutcracker in Havana is brilliant. Innovative, inventive, imaginative, nothing is lost; Tchaikovsky’s instantly recognisable melodies are there, the structure of the plot is there; the beauty and the bombast, the magic and mystery, are all there. And it all works, for whether you are in early 19th Century Nuremberg of early 21st Century Havana, you can still dream of The Magic Castle in the Land of Sweets, somewhere beyond an Arctic pine-forest snowscape.

We, however, are taken straight to Havana in the overture in a video projection as we fly over Old Havana with its colonial buildings, all surprisingly bereft of people. By projecting onto slit drape arches and gauzes, designer Nina Dunn and her team of scenographers create wonderful three-dimensional worlds, cities, jungle, snowscapes that you could lose yourself in.

The atmosphere of this ballet is set from the beginning in the hacienda in the countryside outside Havana where Clara lives a simple life with her extended family. Christmas is back after two decades of Marxist repression of its celebration, and the family have all come together to have a joyous time. The children have a boisterous rough-and-tumble, and the oldies banter with each other about having put on weight, while the mums and dads try to keep everyone in order, all of which provides tailor-made opportunities for some great visual gags.

Then the enigmatic figure of the magical uncle arrives. The traditional Drosselmeyer is here as the debonair Uncle Elías, arrived from exile aboard with a backpack of pressies for all the family. Everybody falls under his benign spell as, with a sweep of his hand, he transforms their shack into a splendid mansion, complete with sweeping grand staircase, and their patched-up denims into snazzy new suits and party gowns. Even their sparse Christmas tree grows and grows (no doubt Acosta remembers the ROH’s Nutcracker tree).

Alexander Varona, a Critics’ Circle Dance Award winner, makes a splendid Tío Elías Drosselmeyer, an omnipresence in the story, sometimes observing and often controlling events, slick, suave and somewhat self-satisfied (and sometimes slightly sinister).

The family are only too happy to take advantage of Drosselmeyer’s transformations, of themselves as well as their surroundings. The grandparents dance the Grossvatertanz, with Aymara Vasallo and Aniel Pazos, and Paul Brando and Daniela Francia taking full advantage of the (ageist?) humour.

The eponymous Nutcracker soldier is there of course, Clara’s present, broken in the children’s horseplay and magically instantly repaired by Drosselmeyer. However this Nutcracker has the form of a guerrilla from the mambíses, the heroes of the Cubans from their 19th Century wars with Spain. They had cross bandoliers, hat with an upturned front brim and machetes as their weapons.

The gingerbread soldiers in this version become mambíses, led by the transmogrified Nutcracker as the mambí colonel, danced by Enrique Corrales. Carla has meanwhile been terrified by gruesome giant rats and the customary battle ensues, the King Rat danced by Denzel Francis. Between the mambíses’ machetes and the rats’ claws the battle becomes truly horrific, but gives opportunity for energetic displays of dance with impressive grand jetés from Corrales and Francis.

This may all sound like variants on the classical ballet, but what makes Nutcracker in Havana so special is the son Cubano, the unique rhythms of Cuba, such as criolla and guaracha. Pepe Gavilondo’s arrangements seamless blend in these rhythms with Tchaikovsky’s score. The original score is surprisingly flexible, and similar ideas have been tried before, notably Duke Ellington’s jazz version. But Gavilondo takes it to a new level. His version, pre-recorded (actually in Havana) by the Cuban Nutcracker Ensemble, includes Yasel Muñoz further augmentations.

Where it most striking, visually and aurally, is in the use of the chancleta dance. Chanleta are sandals, cum flip-flops, cum clogs, fitting loosely over the ballet slippers and pumps, which makes a loud clattering sound. Yes, with Acosta’s magic you can blend this with classical French ballet!

This technique comes as a surprise variant in the early scène dansante, when a chest is produced and everyone on stage takes out their chancleta and joins the fun. Clearly it is a folksy thing the family has all done before. But it prepares us for its reappearance in Act Two in one of the set-piece speciality dances.

The transition between the Acts, the Waltz of the Snowflakes returns to a somewhat more classical style. Comprising male dancers and ballerinas, the corps de ballet’s all white tutus have trailing trains of snow crystals, which give an enchanting effect. Costume designer Angelo Alberto has a flair for just adding in these touches that lift the concept even further, and Andrew Exeter’s lighting designs further enhance the enchantment.

Another immersive 3D trip flies us in Clara’s imagination out of the Caribbean to snow covered pine-forests and on to the Land of Sweets to the Magic Castle, looking a little like the Liverpool RC Cathedral stranded in the Arctic. Inside, Clara is seated by Drosselmeyer on a juke-box like throne, ready to enjoy the divertissements. As might be expected these are a little different from their traditional treatments. They have added Cuban pizzazz, although Acosta prudently does not stray too far from the classical presentation, at least in the openings of each number.

Melisa Moreda and Brian Ernesto’s Spanish Dance has fire, but Amisaday Naara and Paul Brando (now miraculously youthful after his earlier role) up the stakes with a beautiful Arabian Dance, full of soft and sinuous sensuality.

There is quite a departure from the usual Mirlitones Dance. The reed pipe dancers are not a quartet of tutu-ed ballerinas, but a trio of harlequins, Elizabeth Tablada, Alexander Arias and Thalía Cardín, who bring out the playfulness of the piece, with a humorous and athletic interpretation using contemporary dance techniques such as tumbling and popping. It all seems to happen with a sort of tipsy exuberance.

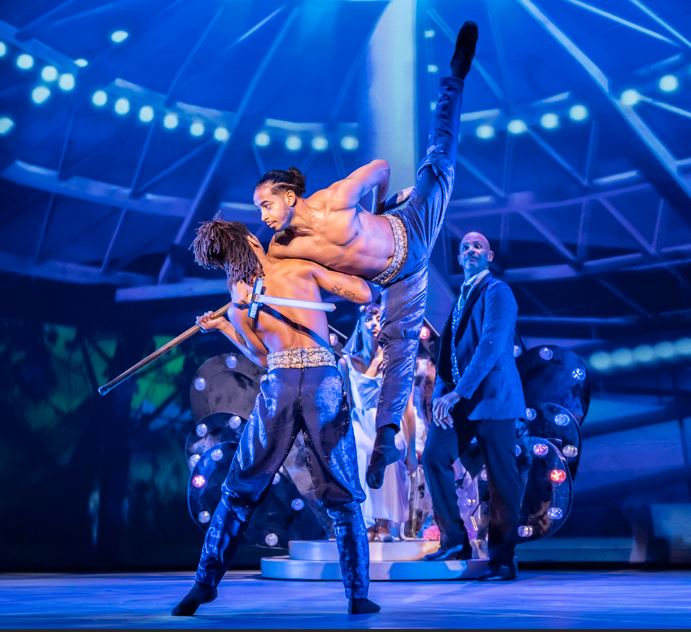

The Chinese Dance is equally unexpected as Leandro Fernández and Brandy Martínez perform as kung-fu swordsmen, the dance and martial arts forming a mesmerising duet in which they seem to dance around, over and through each other.

Adria Díaz, as a charming Clara, watches all this wide-eyed, her body language vividly expressing the joyous juvenile excitement. Díaz’s portrayal is flutteringly fawn-like, light and delicate, a young girl clapping her hands in delight.

Another stand-our divertissement is the Russian Dance. Raúl Reinoso’s muscular attack on the Trépak, the Russian Cossack dance, is quite breath taking, interlacing grand jeté en avant and grande pirouette in a powerful whirlwind.

The much loved Waltz of the Flowers starts as the set-piece classical exposition, stylishly executed by Patricia Torres and a returning Enrique Corrales and a sextet of Flower Girls in lovely whirling pink patterns. Then gradually, the family join in as it becomes, almost imperceptibly, a conga and then equally effortlessly runs into the chancleta, a gorgeous sight with the whole company filling the stage. This is a far cry from the clog dance in La Fille Mal Gardée and there is the extra peril of Richmond Theatre’s notoriously steeply ranked stage.

Then of course everyone waits for the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, and in contrast the mood reverts to pure classical form. The fluent femininity of Laura Rodríguez’s Sugar Plum Fairy is enhanced, in the preceding intrada, with the foil of Alejandro Silva as the Prince. Their pas de deux beautifully combines lyricism and power (and impressively giddying fouettés).

To call Carlos Acosta’s Nutcracker in Havana a crossover piece would downplay the skill in combining the lyrical classical ballet with contemporary techniques and folk dances; orchestra, jazz and son Cubano working together. None of them tread on each other’s toes (figuratively speaking of course). Oh, and did I mention Javanese shadow theatre and English maypole dancing (twice). All the elements mingle delightfully, as sweet and smooth as a syllabub.

The overall picture is one of joy. It is the joy of a people shaking off tyranny. The second half of the Twentieth Century was traumatic for the Cuban people under the psychopathic despotism of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara and their followers, a yoke it is even now trying to shake off. Carlos Acosta explains how, during his childhood in the 1960s and 70s, Christmas was banned and its celebration virtually unknown even into the 1990’s when it was recognised and celebrations began to be resumed. As such Carlos Acosta’s blockbuster is a tribute to the resilience of the Cuban people and of its innate sense of joy and fun that had been repressed for so long.

Nutcracker in Havana deserves to become a Christmas staple alongside the Petipa and Balanchine standards we have all grown used to. And I will be the first to lead the conga around the Christmas tree.

Mark Aspen, November 2024

Photography by Johan Persson

Trackbacks & Pingbacks