Turandot

Resplendent Restaging

Turandot

by Giacomo Puccini, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni

Instant Opera at the Courtyard Amphitheatre at the TownHouse, Kingston until 12th October

Review by Richard Copeman

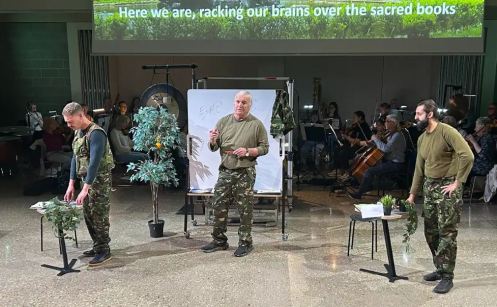

Instant Opera revived its ambitious production, sung in Italian, of Puccini’s final (unfinished) opera, Turandot, in a new venue, designed by Grafton Architects, which has won several prestigious architectural awards for its clean and open format. The Courtyard, an auditorium in the Town House at Kingston University, offers a large performance space for the chorus and soloists, especially with the 38-piece orchestra behind the acting area. The steeply stepped arena with hard seating on three sides gave excellent sightlines and clear surtitles were projected onto a large screen, together with images of the moon and various backgrounds, including devastated cities. Writing in the programme, Instant Opera’s artistic director and producer, Nicholas George explained his concept of a post-apocalyptic dystopian society set in 2184,. This imagined a cruel, medieval type society not dissimilar to the original Gozzi Chinese setting. The first difference I noticed was the comedia del arte trio of ministers being in paramilitary costume.

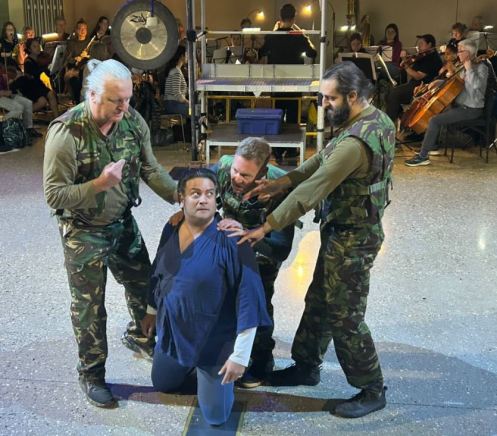

Three performances were given with a double cast. From the first chords I was impressed with the sound of the reduced orchestration and the chorus, which had several outstanding singers, and a delightful children’s choir, all under the control of conductor Kelvin Lim. The first soloists to appear were the firm bass Timur, Ian Henderson (who was also responsible for restaging the production in the new venue); and his faithful slave, Liu, Eva Gheorghiu, who sang with a lovely pure voice and ravishing soft high notes which put me in mind of her Romanian namesake, Angela! The unknown Prince, Calaf, reunited with his father Timur, was sung by Instant Opera favourite, Indian tenor Anando Mukerjee. His ample, bronzed tenor has now developed into a dramatic spinto, ideal for this role. In his first aria, addressed to a weeping Liu, he was able to soften his voice to a tender love song.

In the meantime, the chorus had delivered their prayer to the moon and called for the blood of another victim of the man-hating Turandot, who showed herself dressed in fetching black leather, rather than the traditional Chinese court dress. She was sung by another singer of Indian origin, British Asian soprano Meeta Raval. Although she is silent in Act One, she makes up for it by dominating Act Two with her aria explaining her distrust and fear of men due to her ancestor’s abuse. In this demanding music Raval displayed a focused, steady voice with a touch of steel, which rode the orchestra and delivered the top notes brilliantly. She was presented less of a harridan than usual, and more a feminist, which made her a plausible character. In the three riddles which Calaf must solve to win her, or die, she seemed to show signs of warming to the prince, even giving a hint when he seems to falter on the last answer. Calaf decides to offer her a way out, when she pleads for mercy, if only she can learn his name …. he announces this with a triumphant top C!

Throughout the action, the trio of ministers, Ping, sung by experienced Australian baritone Jeffrey Black and Pang and Pong, by tenors Gary Rushton and Ernesto Vacarezza were all able to sustain interest in their nostalgic scene as we all waited in suspense for the climactic riddle scene. Here we also met the emperor, another tenor Peder Holterman, as Turandot’s elderly father who tries to dissuade Calaf from sacrificing his life. Dressed in a traditional Chinese robe, he was less doddery than usually presented and sang in a clear voice. The baritone Mandarin Yuki Okuyama did justice to his two announcements and four dancers from the Kingston Ballet School added to the spectacle throughout.

The last act gave us the popular tenor aria, Nessun dorma that we were all waiting for and Anando Mukerjee did not disappoint, giving a ringing climax. Next comes the interrogation and suicide of Liu, who once again gave a beautiful account of her second aria. Her demonstration of love (unrequited) for Calaf helped break down any remaining doubts about Turandot’s own feelings.

Timur’s moving lament for Liu is the point at which death took Puccini, preventing him from completing the opera. At the La Scala premiere in 1926, Toscanini ended there, although Franco Alfano had been commissioned to compose music for the final text. Alfano was a friend and colleague, and Puccini had already sought his advice as Alfano had himself once considered Turandot as subject for an opera. Puccini had left only fragmentary sketches and had been daunted by the problem of resolving Turandot’s change from hate to love following Calaf’s kiss in the final scene. This may be a male fantasy but is not convincing from a dramaturgical point of view. A clue to his thinking is found in one of his musical sketches when he writes “now Tristan”. I feel he was not referring to Wagner’s great love duet, but to the scene in Act One of Tristan und Isolde, where Isolde’s fury and curses directed at Tristan turn to adoration after drinking the potion. Wagner does this with an orchestral interlude, and Alfano wrote one after the kiss. However, Toscanini ruthlessly cut about a third of Alfano’s ending, stating it did not sound like Puccini, and this is the version usually given, as it was here. The full Alfano ending has been reconstructed, and recorded, and I find it more convincing, although taxing for the singers. Alfano had a thankless task, and when a friend stated that he would always be remembered for finishing Turandot, he replied… “No, Turandot finished me!”

In this production the transformation was convincing and her final thrilling revelation that his name is love ended the opera (literally) on a high note, to round off a very enjoyable evening.

Richard Copeman, October 2025

Photography by Jon Lo Photography