Enron

Oil Slick

Enron

by Lucy Prebble

Richmond Shakespeare Society at the Mary Wallace Theatre, Twickenham until 28th October

Review by Ian Moone

It has been said that when America sneezes, the world catches a cold, and it was certainly a gargantuan sneeze that spread the global financial virus of 2008, resulting in the meltdown or recession of many of the world’s economies. The reasons for this crisis are many and various but the events at Enron, only seven years prior, described so succinctly by Lucy Prebble in this award winning play, certainly started Uncle Sam’s financial nasal hairs tickling.

At its peak in the summer of 2000, Enron’s share price soared at $90.75, valuing the company at $70billion and making it, on paper at least, one of the most successful companies in US history. However, only eighteen months later, the share price had plummeted to just $0.26 and, days later, the company was declared bankrupt, sending shock waves through the global financial markets. To this day, many still wonder how a business that had lead the way on technical and corporate innovation could have failed so catastrophically. Even more puzzling is how one of the most elaborate frauds in corporate history had escaped financial scrutiny for so long.

Prebble’s cautionary account of this monumental collapse takes us on a lightning-paced journey of revelation, during which she attempts to condense the complexities of Enron’s jaw-dropping underhand dealings, fake holdings and off-the-book accounting practices into approximately two and a half hours.

Formed in 1985 with the merger of Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth, and under the leadership of CEO & Chairman, Kenneth Lay, Enron was perfectly poised to maximise the potential of the controversial and highly anticipated deregulation of US energy markets. In 1989 Lay made a conscious move to branch away from the traditional business approach of producing and distributing gas, and established a division to focus mainly on the trading of natural gas commodities instead. Soon realising the huge potential within this market and identifying the need for fresh ideas and leadership to further develop this strategy, Lay recruited Harvard Business School graduate, Jeffrey Skilling, setting him two clear goals: to identify any opportunities arising from market deregulation and to maximise the resulting profits.

Crucial to Skilling’s early success was his insistence on the implementation of a new accountancy philosophy, known as ‘marked-to-market’. This allowed Enron to claim the earnings on ‘tomorrow’s’ revenues and immediately list them on ‘today’s’ balance sheet. With every new and innovative idea, more future profits were immediately accrued, resulting in a highly skewed representation of their success. It wasn’t long, therefore, before Wall Street began falling over themselves for Enron stock. This new marketing system sent the share price through the roof, but it had one major flaw… when these future profits were seldom actually realised, there was very little cash flowing into the business. With high operating costs and no cash to finance them, the reality very soon began to fall well short of the perception. When perception is the only thing keeping the share price so grossly overinflated, it became vital to protect it at all costs.

Furthermore, with over 20,000 employees on its books and with little means to pay them, Skilling had another big problem on his hands. If dissatisfied staff were to begin making waves, he knew that this would soon attract unwanted scrutiny. So how would he keep them on side? Well, in lieu of wages, Skilling decided to offer stock options to all staff instead, and these options were eagerly snapped up. Not only did this mean that staff were, temporarily, satisfied but it also created an environment where everyone became fiercely loyal to the cause and unhealthily fixated on maintaining or increasing the share price.

Introducing this employee share option had the added benefit of bringing much needed cash into the business. In the first nine months of 2000, Enron generated just $100m in cash. However this figure would have been negative if not for the $410 million in tax breaks it received as a result of employees exercising their option. This short-term fix now in place, Skilling needed to close the gap between reality and perception, and fast!

This opportunity presented itself through a chance conversation with one of his financial team, Andy Fastow. A financial nerd, Fastow had been experimenting with various hedging models and had toyed with the idea of creating financial entities for the sole purpose of hedging against the bad-assets and debts of his own small funds. When approached by his idol, Skilling, Fastow convinced him that this experimental model would work and that, for the cost of a few million dollars, they could hide all of Enron’s short-comings at the heart of his Russian-doll-like structure of shadow companies that were made up, incredibly, of 97% of Enron stock, with the other 3% being funded by various US financial institutions. This newly formed company, LJM (the initials of Fastow’s wife and children), was headed by Fastow himself, with Enron’s board of directors giving Fastow an exemption from their own ‘conflict of interest’ rules. Skilling rewarded Fastow’s genius by making him Enron’s Chief Financial Officer and everything was set for one of the largest corporate frauds in American history.

On paper, everything Skilling touched turned to gold and Wall Street’s analysts responded positively, with thirteen of the eighteen Enron analysts consistently rating stock as ‘Buy’. As a result, the share price went from strength to strength. Marked-to-market continued to facilitate the immediate realisation of future profits, such as Enron’s partnership with movie giant, Blockbuster, to stream movies across a then juvenile internet and without sufficient bandwidth available to do so. Hundreds of millions were spent on this and other ill-fated ventures, with the partnerships eventually failing. However, with their future forecasted profits already declared on Enron’s balance sheet and the associated bad-debt or high initial overhead and set-up costs being swallowed up by Fastow’s shadow entities, his so-called ‘Raptors’, the façade of continued success was maintained.

The gap between perception and reality, however, continued to grow and the need to bring cash into the business became ever more desperate. This opportunity arrived when George W. Bush was elected president. Fellow Texans and long-term friends of Lay, the Bush family were Enron allies. “Junior’s” bid for presidency was heavily backed by Lay and, soon after his inauguration, Bush rewarded his loyalty with the holy-grail of energy deregulation – the state of California. With this, Skilling and Lay gave the green-light to Enron’s traders to rape and pillage the electricity market. Trading electricity meant that they could ship it out of State, limiting the available capacity and therefore over-inflating the cost-per-unit. Rolling black-outs were experienced throughout the state with hospitals and emergency services even suffering at the hands of Enron’s greed. Quite simply, if the state of California wanted electricity, they would have to pay handsomely for it!

This much needed cash injection was a huge relief to Skilling, and his market exploitation therefore continued relentlessly. This was 2001 and Enron’s share price was at an all-time high. Everything was finally falling into place. That is until a Wall Street journal reporter, by the name of Bethany McClean ran an article titled, “Is Enron Overpriced”. The essence of the article was that Enron’s accounts were a ‘black-box’ and appeared to be little more than smoke and mirrors. Enron had always been fiercely protective of their business model, claiming to want to protect their complex business strategies from their competitors but the truth, of course, was that they knew that if anyone scratched the surface, they would quickly realise that there was very little underneath.

Being given the opportunity to offer Enron’s side of the story prior to publication, Skilling dispatched Fastow to New York to persuade McClean that her opinion was incorrect. However, unable to offer any proof to substantiate this and, therefore, to stop the publication, it went ahead. Skilling was ordered by an anxious Lay to manage the fall-out. A conference was hastily arranged in a desperate attempt to steady the nerves of Wall Street’s analysts, but when pressed on the lack of transparency, Skilling angrily called one of them an ‘ass-hole’. As news of this spread, the share-price plummeted and, following Skilling’s hurried resignation, Enron fell like a house of cards.

In 2006, Skilling and Lay were both prosecuted for their involvement in the fraud, with Fastow turning chief federal witness. Skilling was convicted on nineteen of the twenty-eight counts of securities and wire fraud and was acquitted of the remaining nine, including insider trading. He was sentenced to over 24 years in prison and served just twelve.

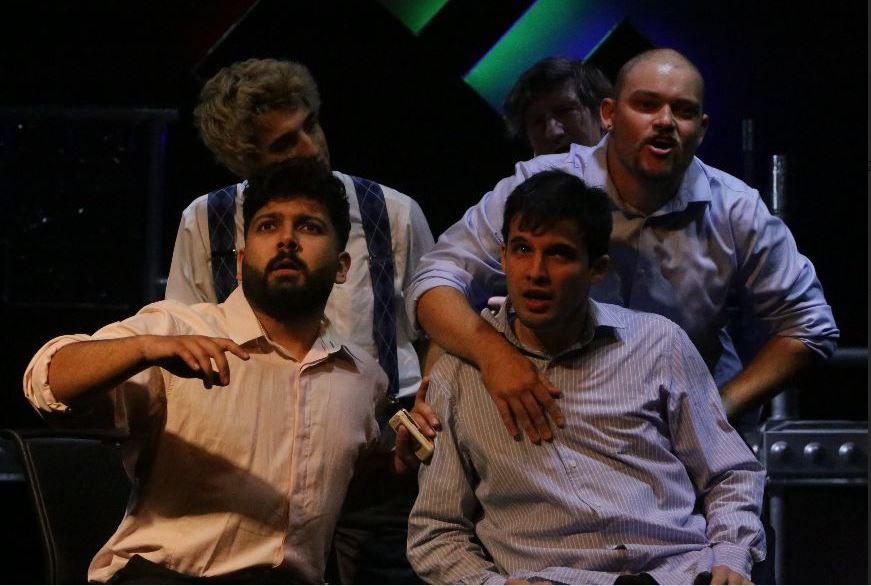

Directed by Maxina Cornwell, RSS’s interpretation of this complex piece was hugely enjoyable and very well delivered by a strong main cast and talented ensemble. In order to flow seamlessly, the play requires multiple, fast-paced scene changes, best suiting a large stage or even a revolve. Attempting to undertake it on a stage the size of that at the Mary Wallace theatre, therefore, was hugely ambitious and testament to the outstanding production team of Junis Olmscheid and Marc Pearce for successfully achieving this. The multi-level set design, coupled with sophisticated stage-lighting techniques allowed the seamless and rapid movement between multiple locations, from the humble beginnings of a dust-sheet covered, antiquated office space to the projected stock-price images and fully working VMS (matrix) board, displayed atop a highly convincing modern trading floor. The scene changes came fast and furious and were slickly choreographed and well-rehearsed.

As Skilling, Charlie Golding gives a solid performance of the main protagonist. His laid back, self-loving approach at the beginning of the play allowing sufficient room to reflect the emotional journey through anxiety and, eventually, to frustration and desperation. Skilling is a self-professed genius, viewing himself as ‘the smartest guy in the room’. As the house of cards begins to fall, his resentment towards the no-hopers that staggered their way into positions of power in the US government is evident in his ranting monologue. Skilling’s attitude towards the “frat-party, know-nuthin’ fucks” who write policies for things that “they know nuthin’ about”, was also well delivered by Golding, showing the audience that Skilling’s behaviour was, perhaps, as much to do with proving himself as a success to the popular guys who didn’t want to know him at Harvard as it was to proving himself as an able businessman on the world stage.

Playing Claudio Roe, Prebble’s fictional representation of the ‘few good men’ of Enron, is the highly talented Amanda Adams. Throughout the play, Roe regularly challenges Skilling’s position on many important issues, challenging him for the position of CEO and emphasising the importance of maintaining Enron’s traditional assets. Roe is a powerful voice on Enron’s management team and can see the frailties in Skilling’s dictated direction of travel. She is eventually forced to leave when Skilling tasks Fastow with digging deep into the accounts of her department, finding minor irregularities and forcing her resignation as a result. Ironically, following the collapse of Enron, these traditional sections of Enron’s business were the only areas that were actually making money. Adams’ portrayal of Roe is excellent, displaying both the powerful, determined, ambitious business woman and caring, thoughtful and questioning sides of her character equally well. Roe cares deeply about the company and her world is torn apart when she is forced to leave. However, she is all too aware that Skilling is steering the good-ship Enron towards a financial iceberg. Her parting remark to him upon the rooftop terrace of the Enron skyscraper, is that she is going home to her daughter and will be selling all of her shares. Like many in the company, she had been blinkered by the share-price for so long but, now, finally awakening to the reality, represents the few who managed a lucky escape.

Skilling was, of course, highly instrumental in the collapse of Enron. However, as previously discussed, the scale of the fraud could never have reached such a monumental level without the assistance of Andy Fastow. His ‘off-balance-sheet, special purpose entities’, affectionately known to him as his ‘Raptors’, were key to hiding or consuming the mountains of bad-debt from the many poor business ventures and partnerships that Enron entered into, keeping the ‘bad stuff’ off the books and thus ensuring that Enron’s share-price always looked skywards. Fastow was a financial geek and, in the words of Skilling, was not a people person. His strength lay in his financial ability to think outside the box, always on the look-out for financial loop-holes to exploit. Professionally, he was a loner, appearing at his most satisfied when locked away in his office tending to his raptor accounts. In her play, Prebble very literally brings these raptors to life, and in RSS’s production these three sinister sisters are played superbly by Harriet Evans, Anastasia Babich and Vinutha Hegde. In other productions, directors have opted to create elaborate and, one suspects, very expensive costumes to represent these three creatures but, rather, Maxina Cornwell has opted for a more simple yet no less effective representation instead. Simply dressed all in black and with a set of vicious claws each, their believability lies more in the strength of their physical acting attributes than in the costumes themselves. As a firm advocate of physical theatre it is evident throughout this production that Cornwell has spent hours working on many aspects of this side of the piece. Clever, subtle head and neck movements and perfectly matched postures not only make them believable but entirely intriguing to the audience. Their relationship with their master and creator, Fastow, who feeds them money to clearly demonstrate their ability to destroy bad-debt, is a joy to watch. Allowing themselves to be petted by him at the beginning, and protecting him from intruders to their lair (Fastow’s dungeon-like office), their demeanour visibly changes as things start to go wrong and, as one of them becomes sick from the amount of debt they’ve consumed, the others start showing signs of aggression towards the hand that feeds.

Bringing the raptors to life allows the importance of their existence to be better understood and allowed Prebble to clearly explain some complex financial themes to her somewhat less financially-savvy audiences. Playing Fastow, the controller of these beasts, is Aleksei Toshev and his performance was nothing short of perfection. American accents can be difficult to maintain for an entire performance and it’s fair to say that a number of other actors, mainly in the ensemble, struggled to pull them off at all, never mind hold them for the duration of the play, but Toshev’s was on point throughout. Not only this, but his portrayal of the excitable and geeky financial whiz was very well measured and perfectly delivered. Accessing his office/lair through a trap-door, gave the audience a feel for the reclusive nature of this individual. Always desperate to please his master, Fastow’s slightly grating, desperate, side-kick-like persona was delivered by Toshev with aplomb.

Also excelling in his portrayal was Francis Abbot as the brow-beaten Kenneth Lay. A God-fearing man of the South, Lay was, himself, a victim of Skilling’s greed and thirst for power. As a successful businessman, he was, of course, no stranger to corporate malice but had always been proud of the way that Enron had conducted its business dealings. Their model had always been one of asset ownership and he was, therefore, naturally nervous about the speed with which Skilling began to liquidate these physical assets, moving instead towards the trading of energy, bandwidth and anything else that was outside of government regulation. At the start of the play, we see Lay as the proud head of a vast multi-national organisation, still very much in control of its fortunes. However, following his appointment of Skilling to CEO, he takes a back seat and, over time, we see his frustration turn to desperation as he realises that his beloved company is doomed to fail. Abbot’s performance aptly displays this subtle shift from proud southern gentleman to a desperate, broken and defeated man. It is widely believed that when Enron collapsed, he was so personally affected by the realisation of the number of lives that had been ruined, that it brought about the untimely end of Lay’s own life, shortly before his sentencing was due to be delivered.

As good as the main cast were, the success of this piece lies equally with the hugely talented ensemble. Each playing multiple roles, the energy and enthusiasm that they brought to each of them and, therefore, to the play as a whole, was superb. From stereotypical 90’s stock-traders to early 2000’s IT-boom geeks, from TV reporters to desperate Enron employees, each part was played with style and finesse and each clearly distinguishable from the others. Their energetic performances were exhausting to watch and kept the pace of the play lightning fast and, therefore, highly watchable from start to finish.

Congratulations to RSS for having the bravery to take on this ambitious piece of theatre and for having the expertise and strength of membership to do it justice.

Ian Moone, October 2023

Photography courtesy of RSS

It was good to read this review of Enron especially as the production was a sell out, and thus, frustratingly, I was unable to see it … perhaps a longer run!